Function, Method, Closure, Coroutine and Iterator in Rust

A short, practical reminder with working examples.

TL;DR

- For beginners, tinkerers, hobbyists, amateurs, and early-career developers…

- Function: Executes once, returns once

- Method: Function tied to a type

- Closure: Function that captures environment variables

- Coroutine: Function that can suspend and resume, maintaining state across suspension points

- Iterator: Produces a sequence of values lazily, one at a time

Note The companion project with all the examples is available on GitHub.

1992: When Batman returned and Windows 3.1 relied on cooperative multitasking via coroutines.

Table of Contents

- Function

- Function Pointer

- Method

- Associated Function (“Static” Method)

- Closure

- Coroutine

- Iterator

- Are iterators based on coroutines?

Function

- Runs from start to finish in one go

- Returns a single value

- Stack is destroyed when it returns

- No state preservation between calls

Example: You can copy and paste the code below into the Rust Playground:

// cargo run --example ex00

// Function

fn regular_function(x: i32) -> i32 {

println!("Regular function computing {} * 2", x);

x * 2

}

fn main() {

let result = regular_function(5);

println!("Result: {}\n", result);

}

Expected output:

Regular function: computing 5 * 2

Result: 10

Function Pointer

- A primitive type (

fn) that points to the address of a function - Does not capture any environment variables (unlike closures, see below)

- Has a fixed size (the size of a pointer)

- Can be passed to other functions as arguments or stored in data structures

- Functions that don’t capture anything can be coerced to function pointers

Example: You can copy and paste the code below into the Rust Playground:

// cargo run --example ex_01

// Function Pointer

fn add_one(x: i32) -> i32 {

x + 1

}

fn do_math(f: fn(i32) -> i32, arg: i32) -> i32 {

f(arg)

}

fn main() {

// Passing a named function as a pointer

let result = do_math(add_one, 5);

println!("Named function result: {}", result);

// Closures that don't capture state can also be function pointers

let closure_ptr: fn(i32) -> i32 = |x| x * 2;

let result_closure = do_math(closure_ptr, 10);

println!("Closure pointer result: {}\n", result_closure);

}

Expected output:

Named function result: 6

Closure pointer result: 20

Method

- A function associated with a type/object

- Same execution model as functions (runs to completion)

- Can access

selfdata - Methods take

selfas their first parameter, whereas Associated Functions (see below) do not

Example: You can copy and paste the code below into the Rust Playground:

// cargo run --example ex02

// Method

struct Calculator {

multiplier: i32,

}

impl Calculator {

fn multiply_method(&self, x: i32) -> i32 {

println!("Method computing {} * {}", x, self.multiplier);

x * self.multiplier

}

}

fn main() {

let calc = Calculator { multiplier: 3 };

let result = calc.multiply_method(7);

println!("Result: {}\n", result);

}

Expected output:

Method computing 7 * 3

Result: 21

Associated Function (“Static” Method)

- A function defined inside an

implblock that does not take aselfparameter - Called using the

Type::function()syntax (namespace syntax) - Often used for constructors (like

new()) or factory methods - Similar to “static methods” in other programming languages

Example: You can copy and paste the code below into the Rust Playground:

// cargo run --example ex03

// Associated Function

struct User {

username: String,

active: bool,

}

impl User {

// This is an associated function (no self)

fn new(name: &str) -> Self {

println!("Associated Function: Creating a new User instance for {}", name);

Self {

username: name.to_string(),

active: true,

}

}

}

fn main() {

// We call associated functions using the :: operator

let user = User::new("Alice");

println!("User name: {}\n", user.username);

}

Expected output:

Associated Function: Creating a new User instance for Alice

User name: Alice

Closure

- A function that captures variables from its environment (current block)

- Still runs to completion like a regular function

- The captured state exists across multiple calls to the closure

Example 1: You can copy and paste the code below into the Rust Playground:

// cargo run --example ex04

// Closure

fn demonstrate_closure() {

let captured_value = 10;

let closure = |x: i32| {

println!("Closure computing {} + captured {}", x, captured_value);

x + captured_value

};

println!("Closure result: {}", closure(5));

}

fn main() {

demonstrate_closure();

}

Expected output:

Closure computing 5 + captured 10

Closure result: 15

Example 2: You can copy and paste the code below into the Rust Playground:

// cargo run --example ex05

// Closure

pub fn shift_all<F>(data: &mut [i32], mut mutator: F)

where

F: FnMut(i32) -> i32,

{

for v in data {

*v = mutator(*v);

}

}

fn main() {

let bias = 42;

let add_bias = |n| n + bias;

let mut my_data = vec![1, 3, 5, 7];

shift_all(&mut my_data, add_bias);

println!("{:?}", my_data);

}

Expected output:

[43, 45, 47, 49]

Note

- Rust has three traits for closures:

Fn(reads),FnMut(modifies), andFnOnce(consumes). - Rust chooses the most restrictive one automatically based on what you do inside the

|| {}. - Read this page

Example 3: You can copy and paste the code below into the Rust Playground:

// cargo run --example ex06

// Generator-style coroutine (using iterator)

fn generator_style(start: i32, count: i32) -> impl Iterator<Item = i32> {

(0..count).map(move |i| {

println!("Generator: yielding value {}", start + i);

start + i

})

}

fn main() {

let mut iterator = generator_style(100, 3);

println!("First value: {:?}", iterator.next());

println!("Second value: {:?}", iterator.next());

println!("Third value: {:?}", iterator.next());

}

Note:

move |i|?(0..count)create aRange<i32>which goes from 0 tocount-1..map(move |i| { ... })transforms each element of the range (igoes from 0 to 3)moveforce the closure to take the ownership of the variables it captures (otherwise it get the variables by reference and it does not compile. Make a test, remove themove)- If

moveis removed the explanation goes like that: The closure attempts to capturestartby reference (&start), butstartlives in the stack ofgenerator_style(). When the function returns,startis destroyed, and the closure would contain an invalid reference (dangling reference). Not a good idea, especially for the next time closure will execute.

- If

moveforces the closure to copystart(becausei32implementsCopy). The closure now has its own copy ofstart, independent of thegenerator_style()function and everybody is happy-happy.

Expected output:

Generator: yielding value 100

First value: Some(100)

Generator: yielding value 101

Second value: Some(101)

Generator: yielding value 102

Third value: Some(102)

Note: In Rust, the distinction between a Closure and a Function Pointer is purely about state. If we need to pass “logic” to a function without needing any external variables, a function pointer is the most efficient way to do it.

Coroutine

- Can pause and resume execution

- Maintains its execution state (local variables, instruction pointer)

- Can yield multiple values over time

- Often used for async operations, generators, or cooperative multitasking

- Primarily implemented through

async/await, which compile to state machines that can be suspended at.awaitpoints.

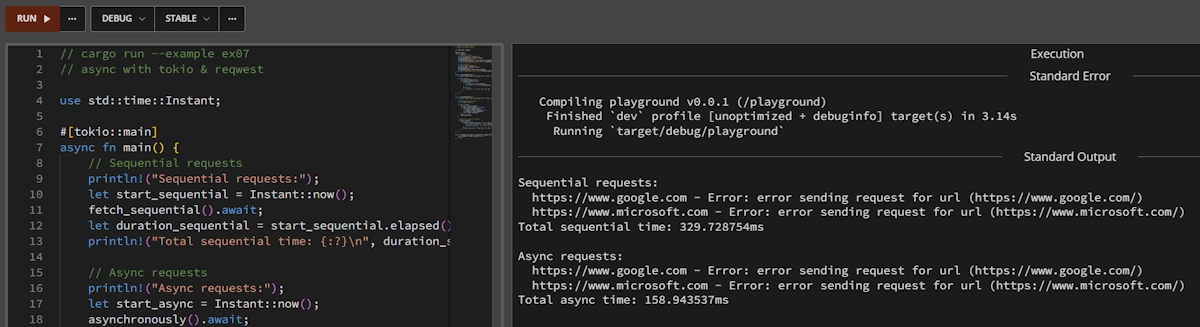

Example: You can copy and paste the code below into the Rust Playground:

// cargo run --example ex07

// async with tokio & reqwest

use std::time::Instant;

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

// Sequential requests

println!("Sequential requests:");

let start_sequential = Instant::now();

fetch_sequential().await;

let duration_sequential = start_sequential.elapsed();

println!("Total sequential time: {:?}\n", duration_sequential);

// Async requests

println!("Async requests:");

let start_async = Instant::now();

asynchronously().await;

let duration_async = start_async.elapsed();

println!("Total async time: {:?}\n", duration_async);

}

async fn fetch_sequential() {

let urls = vec!["https://www.google.com", "https://www.microsoft.com"];

for url in urls {

let start = Instant::now();

match fetch_url(url).await {

Ok(_) => {

let duration = start.elapsed();

println!(" {} - {:?}", url, duration);

}

Err(e) => {

println!(" {} - Error: {}", url, e);

}

}

}

}

async fn asynchronously() {

let urls = vec!["https://www.google.com", "https://www.microsoft.com"];

// Create a vector of futures

let mut tasks = vec![];

for url in urls {

let url = url.to_string();

let task = tokio::spawn(async move {

let start = Instant::now();

let result = fetch_url(&url).await;

let duration = start.elapsed();

(url, result, duration)

});

tasks.push(task);

}

// Wait for all tasks to complete

for task in tasks {

match task.await {

Ok((url, result, duration)) => match result {

Ok(_) => println!(" {} - {:?}", url, duration),

Err(e) => println!(" {} - Error: {}", url, e),

},

Err(e) => println!(" Task error: {}", e),

}

}

}

async fn fetch_url(url: &str) -> Result<(), reqwest::Error> {

let _response = reqwest::get(url).await?;

Ok(())

}

Expected output:

Sequential requests:

https://www.google.com - 147.6548ms

https://www.microsoft.com - 125.9957ms

Total sequential time: 274.657ms

Async requests:

https://www.google.com - 72.3342ms

https://www.microsoft.com - 116.1267ms

Total async time: 116.6558ms

Note At the time of writing, the code above runs in Rust Playground but I get the following error messages. Surprisingly the timing are in the correct order of magnitude (300 vs 150, see below).

Sequential requests:

https://www.google.com - Error: error sending request for url (https://www.google.com/)

https://www.microsoft.com - Error: error sending request for url (https://www.microsoft.com/)

Total sequential time: 329.728754ms

Async requests:

https://www.google.com - Error: error sending request for url (https://www.google.com/)

https://www.microsoft.com - Error: error sending request for url (https://www.microsoft.com/)

Total async time: 158.943537ms

Note Here is the [dependencies] section of the Cargo.toml file of the companion project I use locally.

[dependencies]

reqwest = "0.13.1"

tokio = { version = "1.49.0", features = ["macros", "rt-multi-thread"] }

Note

- Don’t trust the comment under the first picture above, check by yourself and read the article Windows Multitasking: A Historical Aside

- You can also read: How was Multi-Tasking Possible in Older Versions of Windows?

Iterator

- Represents a sequence of values produced one at a time

- Maintains internal iteration state between calls

- Returns the next value on each call, or signals completion

- Often used in for / foreach loops

- Does not necessarily store all values in memory

- Can be implemented by collections, generators, or custom types

- May be finite or infinite

Example: You can copy and paste the code below into the Rust Playground:

// cargo run --example ex08

// Iterator

struct Counter {

current: u64,

}

impl Iterator for Counter {

type Item = u64;

fn next(&mut self) -> Option<Self::Item> {

let value = self.current;

self.current += 1;

Some(value) // Never returns None → infinite iterator

}

}

fn main() {

let counter = Counter { current: 0 };

for n in counter.take(5) {

println!("{}", n);

}

}

Expected output:

0

1

2

3

4

Are iterators based on coroutines?

No, an iterator is not a coroutine in the traditional sense.

Iterator can behaves like a coroutine but but:

- Iterators simulate this through state stored in struct fields

- Coroutines achieve this through actual execution suspension

Iterator

- Pull-based: The consumer calls

.next()to get values - Synchronous: Computation happens immediately when

.next()is called - State machine: Implemented as a struct with state fields

- No suspension points: Code doesn’t “pause” - each

.next()runs fresh logic - Simple trait: Just needs

fn next(&mut self) -> Option<Item>

Coroutine (async/await)

- Push-based: (in async context): The runtime drives execution

- Asynchronous: Can wait for I/O, timers, etc.

- State machine: Compiler generates one from async fn

- Suspension points: Can

.awaitand resume later - Complex: Involves

Future,Poll,Waker, executors

Philosophical Difference

A mind model for Iterator

Each call is a fresh execution of the

next()method. There’s no “pausing” mid-function.

User calls next() → Execute logic → Return value → DONE

User calls next() → Execute logic → Return value → DONE

User calls next() → Execute logic → Return value → DONE

A mind model for Coroutine

A single execution that suspends and resumes, preserving the exact position and local variables.

Start execution → Compute → PAUSE (await)

↓

Resume → Compute more → PAUSE (await)

↓

Resume → Compute more → DONE (return)

Visual Comparison

// Iterator: each next() call executes independently

struct Counter { count: i32, max: i32 }

impl Iterator for Counter {

type Item = i32;

fn next(&mut self) -> Option<i32> {

// This code runs fresh each time

// No "pausing" - just checking state and updating

if self.count < self.max {

self.count += 1;

Some(self.count)

} else {

None

}

}

}

// Coroutine: execution can suspend and resume

async fn async_counter(max: i32) -> Vec<i32> {

let mut results = vec![];

for i in 0..max {

// This is a suspension point - execution can pause here

some_async_operation().await;

results.push(i);

}

results

}

Example: You can copy and paste the code below into the Rust Playground:

// cargo run --example ex09

// Iterator vs coroutine

use tokio::time::{Duration, sleep};

// Iterator: each next() call executes independently

struct Counter {

count: i32,

max: i32,

}

impl Iterator for Counter {

type Item = i32;

fn next(&mut self) -> Option<i32> {

// This code runs fresh on every call to next()

// No suspension, just state checking and updating

if self.count < self.max {

self.count += 1;

Some(self.count)

} else {

None

}

}

}

// Simulated async operation

async fn some_async_operation() {

// Simulate an async I/O or timer-based operation

sleep(Duration::from_millis(200)).await;

}

// Coroutine: execution can suspend and resume

async fn async_counter(max: i32) -> Vec<i32> {

let mut results = vec![];

for i in 0..max {

// Suspension point: the task can pause here

some_async_operation().await;

results.push(i);

}

results

}

#[tokio::main]

async fn main() {

// --- Iterator demo ---

let counter = Counter { count: 0, max: 3 };

println!("Iterator output:");

for value in counter {

println!(" {}", value);

}

// --- Async coroutine demo ---

println!("\nAsync coroutine output:");

let values = async_counter(3).await;

for value in values {

println!(" {}", value);

}

}

Expected output:

Iterator output:

1

2

3

Async coroutine output:

0

1

2

Note

- Is it crystal clear why both outputs are different? Do you feel brave enough to play with the code in Rust Playground so that they become similar?

- I find that this difference is interesting from the learning standpoint:

- The iterator encodes its logic in the

next(). - The async coroutine encodes its logic in the code structure (

for,.await). - Same intent, but the “where” of the control is different.

- The iterator encodes its logic in the