Rust Traits: Defining Character

From basic syntax to building plugins with once_cell and organizing your Rust projects.

This is Episode 00

TL;DR

- Traits define shared behavior across different data types

- Static dispatch: compiler knows all concrete types at compile time (fast, zero runtime cost)

- Functions can accept any type implementing a trait (impl Trait or generics with bounds)

- Dynamic dispatch: use

Box<dyn Trait>to handle different concrete types at runtime - Requires indirection via fat pointers + vtable lookup (slower, but more flexible)

- Useful for collections of heterogeneous objects (

Vec<Box<dyn Trait>>) - Default implementations: traits can provide fallback behavior

- A type can override only what it needs, and rely on defaults for the rest

- This flexibility allows quick prototyping and gradual refinement

Posts

Table of Contents

Introduction

In Rust, traits are an elegant way to define behavior that can be shared across different data types. What I really like is that I can first focus on defining my data types. Later, if I notice they share some common ground, I can extract that into a trait (think of it like a personality trait several people might share). Once the trait exists, I can enrich my data types with it—without touching their original definition. And if an external library already provides a trait, I can still implement it for my own types.

For example, imagine a trait called Loggable. If I have a type Dog, I can make it implement Loggable and suddenly it gains the ability to integrate with logging.

That may sound a bit abstract, so I started experimenting with a very simple project: measuring temperature with sensors that all share a Measurable trait. From there, I wondered whether traits could be used to structure an application around the idea of plugins. Think of an app that needs to support different file formats for reading and writing. Or one that can read data from Ethernet, serial, or Bluetooth connections. In every case, you discover at runtime which protocols/files format/sensor you need to support but they all have commonalities that can be expressed as traits.

Step by step, I experimented and discovered more and more aspects of traits. The result is this series of five posts, each taking about 30 minutes to read. By the end, my hope is not just that you’ll understand how traits work and what they can do, but that you’ll have built the reflex to actually use them. I’m convinced that sometimes all it takes is hearing the same concept explained slightly differently for the “click” to happen—that aha moment.

What’s inside the series?

- Post 0: A gentle start with static vs. dynamic dispatch, and default implementations.

- Post 1: Multiple traits, blanket implementations, orphan rules, and the newtype pattern.

- Post 2: Trait bound inheritance, extension traits, associated types, constants, and functions.

- Post 3: Organizing with modules and crates, and creating sensors dynamically.

- Post 4: Using

once_cellto manage dynamic sensor and actuator registries.

How to read

On the technical side, I assume you’re a beginner. I don’t take anything for granted except that you have Rust and VS Code installed. I start from zero—or almost—and take the time to explain everything line by line. I show how to run code examples, encourage you to experiment, break things, and fix them again.

Each post is self-contained but meant to be read in order. They’re long—sorry!—but I wanted to take the time to explain things thoroughly. Each episode has its own table of contents and links to the others. At the beginning of every section, I show a working example along with its output. When I comment on code, I always include the full listing for clarity. And of course, everything is available in a single GitHub repo.

So here we go. Imagine you’re chatting with a friend or a colleague. I don’t claim to know everything—I’m still learning Rust myself. There will probably be mistakes or things that could be improved. But hey, two heads are better than one, and I’m confident we’ll figure things out together.

A Gentle Start - Static Dispatch

Where data type are known at compile time.

Running the demo code

I’m not going to explain how to run the code every time, so stay with me and pay attention.

- Get the projet from GitHub

- Open the folder with VSCode

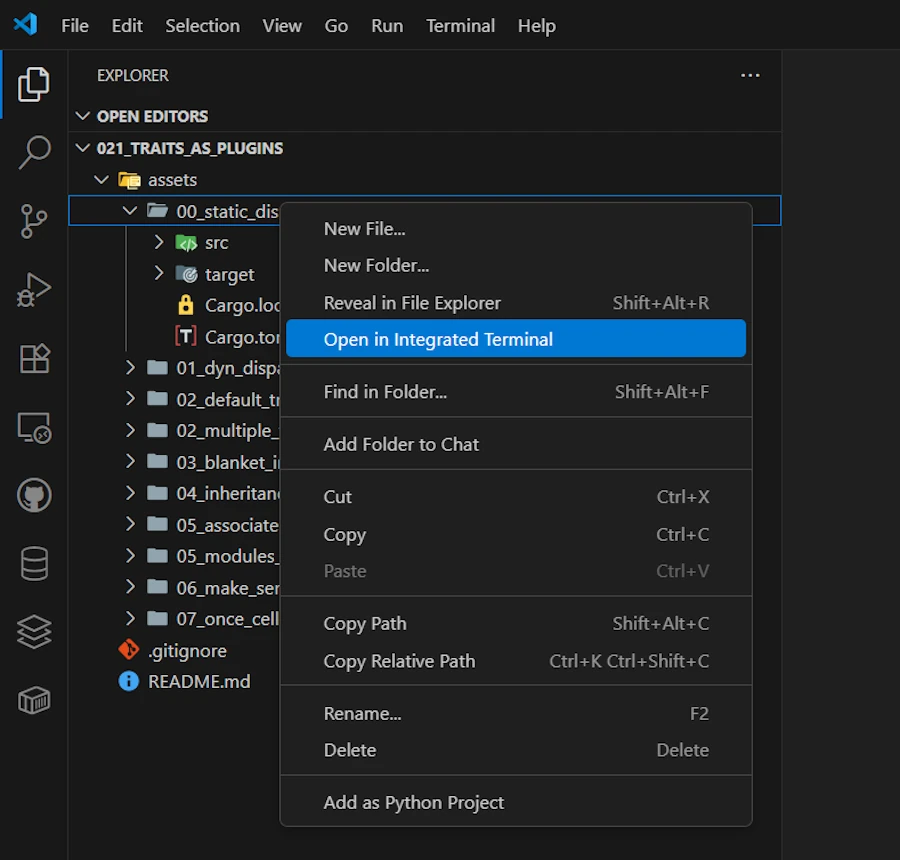

- Once in VSCcode, right click on

assets/00_static_dispatch - Select the option “Open in Integrated Terminal”

Open in Integrated Terminal

Why do I need to open a terminal in a specific directory before to run the code? Simply because the project include multiple projects and some of them are more than few lines of code dropped in a examples/demo01.rs file.

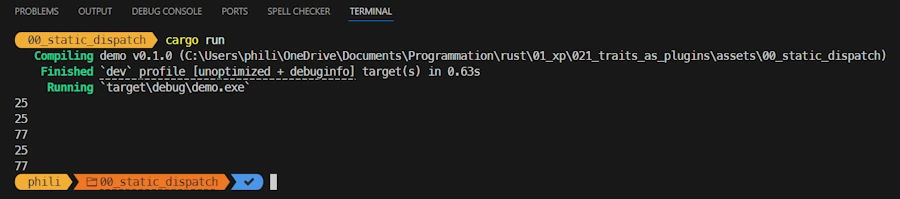

- Enter

cargo run

Click the images to zoom in

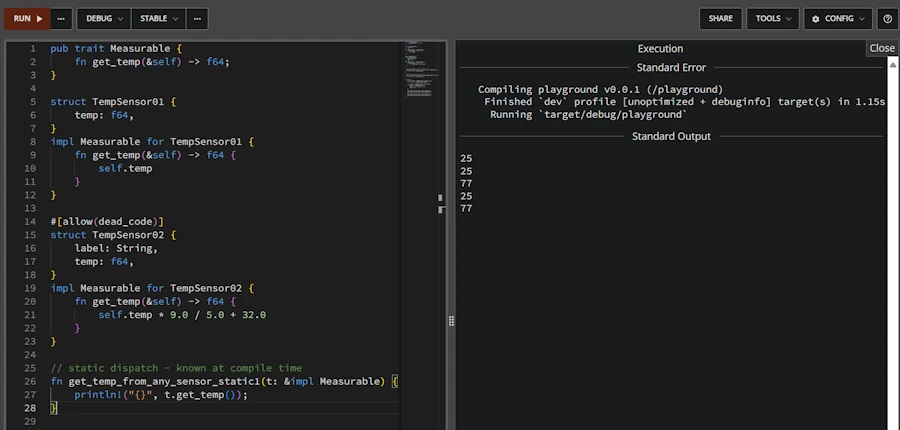

- If you don’t want to run the code locally, until the section about Modules & Crates (Episode 03), you should be able to copy and paste the code in the excellent Rust Playground.

- For this time, and for this time only, you can click the previous link. The source code is already in Rust Playground and so you can press CTRL+ENTER once the web page is open

- Otherwise… Select and copy the code below.

- Paste it in Rust Playground

- Press CTRL + ENTER

Make sure the code compiles and runs otherwise this is less fun.

Running code in Rust Playground

Explanations 1/2

In this section, I suggest approaching the problem from the end user standpoint. Instead of explaining what a trait is and then looking at its use in source code, we will start with a problem. We’ll see how traits provide a solution and then study how they are implemented in the code.

Imagine… Imagine that we work in industry. We deploy monitoring and control systems at various sites around the world. Don’t worry about it. Our task is simple: we install temperature sensors in the factory and we want to read them. Once we have the values, we can display them, store them…

But we have to anticipate… Sure, we’re so efficient and so bright that we’ll be asked to deploy other types of sensors: pressure sensors, strain gauges, flow meters, cameras… And while we’re at it, we’ll be asked to install actuators to close valves, unlock doors, turn on alarms…

First thing first, let’s focus on the temperature sensors. Depending on the region of the world, we are asked to support both °C and °F (nobody’s perfect…). On the other hand, not all sensors are the same. Some of them may be already in place… Some of them may have different communication link (serial, EtherCAT…). Some of them may return values using f64 while other use int16 encoding (microcontroller). So we can imagine that we have different types of temperature sensors, but this should be transparent from the software stand point.

OK… Then what?

What I just described exists under other forms in many other situations. So there are some people who are smarter than others, who took a step back from all this and said to themselves: what you actually want is for all thermocouples to be measurable. It’s a bit like describing people’s characters. Some are touchy, others are cheerful, and still others are candid. They are all different people, men, women, young, old… But they all have certain character traits. Well, you know what, we’re going to give Rust a way to add character traits to existing data types.

For example, I create a Dog type with a struct{}. Then I create a Cat type with another struct{}. Next, I describe what the Deceitful character trait is. Finally, I can then enrich the Dog and Cat types with the trait Deceitful. If I decide that all the cats are deceitful but not the dogs, I only add the trait Deceitful to Cats. I guess, you get the idea.

I would like to underline the fact that from the developer point of view you “extend” existing data type with traits. This can be traits that already exist or some traits that you decide to create because you realized this and this features are present in more than one of your data type and so it makes sense to refactor the code and create a trait. Many traits are already available in Rust std.

Before we look at the first source code example, there is one last point to keep in mind. Given that Rust is quite strict (to say the least) when it comes to type-related issues, we can write functions that take, as parameters, only data type with certain traits. For example, I can write a function that takes, as a parameter, any animal that has the trait Deceitful. It will then be able to deal with Cats, Parrots and all sorts of animal owning the Deceitful trait. Similarly, I can create vectors that only contain animals with the trait Deceitful. This is pretty cool, because I can also rely on the compiler’s rigor to warn me during compilation if I accidentally call the function with an argument whose type does not have the Deceitful character trait. You know the story : Compilers makes sure the good things happen — the logical errors are on you.

Okay, let’s move on to studying the first source code and see how all this apply to our thermocouples.

Show me the code!

pub trait Measurable {

fn get_temp(&self) -> f64;

}

struct TempSensor01 {

temp: f64,

}

impl Measurable for TempSensor01 {

fn get_temp(&self) -> f64 {

self.temp

}

}

#[allow(dead_code)]

struct TempSensor02 {

label: String,

temp: f64,

}

impl Measurable for TempSensor02 {

fn get_temp(&self) -> f64 {

self.temp * 9.0 / 5.0 + 32.0

}

}

// static dispatch - known at compile time

fn get_temp_from_any_sensor_static1(t: &impl Measurable) {

println!("{}", t.get_temp());

}

// static dispatch - generic syntax

fn get_temp_from_any_sensor_static2<T: Measurable>(t: &T) {

println!("{}", t.get_temp());

}

fn main() {

let my_sensor = TempSensor01 { temp: 25.0 };

println!("{}", my_sensor.get_temp());

let sensor1 = TempSensor01 { temp: 25.0 };

let sensor2 = TempSensor02 {

label: "thermocouple".into(),

temp: 25.0, // 77 °F

};

get_temp_from_any_sensor_static1(&sensor1);

get_temp_from_any_sensor_static1(&sensor2);

get_temp_from_any_sensor_static2(&sensor1);

get_temp_from_any_sensor_static2(&sensor2);

}

Explanations 2/2

Here, I will go very slowly. Reading the source code out of order, telling you a story and making sure we all have the same basic understanding.

I first create a data type TempSensor01. It is very basic and it only have a float field representing the current temperature.

struct TempSensor01 {

temp: f64,

}

Then I create a second data type TempSensor02. This one is much more sophisticated. It has fields for the current temperature and its label.

struct TempSensor02 {

label: String,

temp: f64,

}

At this point we have 2 temperature sensors, which are of 2 different data types. They are 2 different beasts, and we cannot use a TempSensor01 in place of TempSensor02. This is a very good thing most of the time but ideally we would like to be able to read temperature measurements from all of them using the same function.

This is where traits comes into play. First, I create a trait named Measurable. Below we are saying something like : If a data type wants to be Measurable it must provide a get_temp() method which returns an f64. We could be stricter here and define our own data type for the temperatures to be returned (think at type Temp = f64; or struct Temp(f64);) but this is not the point here.

pub trait Measurable {

fn get_temp(&self) -> f64;

}

As we can see, a trait is a kind of contract or a kind of interface. We define what is needed without defining the implementation.

That is fine but now, if we want TempSensor01 and TempSensor02 to be Measurable, we must define the get_temp() method for each of them. This is done using the impl (implement, implementation) keyword and then defining the get_temp() method. Both methods are not the same and for example, the get_temp() method from TempSensor02 returns °F (what a pity…).

Additionally if the trait requires other methods we could define them here. There is no restriction but I find it useful to define everything in a single impl block (one per data type).

impl Measurable for TempSensor01 {

fn get_temp(&self) -> f64 {

self.temp

}

}

impl Measurable for TempSensor02 {

fn get_temp(&self) -> f64 {

self.temp * 9.0 / 5.0 + 32.0

}

}

Now let’s look how it works in the main() function. Below I first create my_sensor which is of type TempSensor01. Since I have implemented the trait Measurable for the data type TempSensor01 this means I added the get_temp() method to the data type TempSensor01. This means I can call.get_temp() on my_sensor.

Next I create 2 sensors of respective type TempSensor01 and TempSensor02. And now, this is really cool. Indeed I can use reference to either TempSensor01 or TempSensor02 as argument of the function get_temp_from_any_sensor_static1().

fn main() {

let my_sensor = TempSensor01 { temp: 25.0 };

println!("{}", my_sensor.get_temp());

let sensor1 = TempSensor01 { temp: 25.0 };

let sensor2 = TempSensor02 {

label: "thermocouple".into(),

temp: 25.0, // 77 °F

};

get_temp_from_any_sensor_static1(&sensor1);

get_temp_from_any_sensor_static1(&sensor2);

}

Now the question is : how the get_temp_from_any_sensor_static1() function is defined? See below.

The most remarkable point is that the parameter t is of type &impl Measurable. This is not true, but this is good enough for now. The code below says something like : My name is get_temp_from_any_sensor_static1() and I take a reference to any parameter which implements the Measurable trait (this is true).

fn get_temp_from_any_sensor_static1(t: &impl Measurable) {

println!("{}", t.get_temp());

}

The good thing is that since I know that t has the trait Measurable, then I can call the method get_temp() on t in the body of get_temp_from_any_sensor_static1().

OK, this sounds great but how does it works? In fact, at compile time, when rustc (our best friend, the compiler) see the impl keyword it monomorphizes (expand) the code for every concrete type that implements the Measurable trait.

Imagine that the source code is modified so that it has a definition for fn get_temp_from_any_sensor_static1_1(t: &TempSensor01) {...} then another for fn get_temp_from_any_sensor_static1_2(t: &TempSensor02) {...}. The compiler “copy and paste” source code, it expands the source, it duplicates function calls… Pick the one that click best for you.

Keep in mind that, here, everything is static. I mean once the monomorphization (source code expansion) is done, the compiler compiles the expanded code as usual. The source code is longer, the compilation takes more time but there is no penalty at runtime. More important : from the end user standpoint (you, me, your young sister) everything looks like if the function get_temp_from_any_sensor_static1() could accept any type of argument as long as it implements the trait Measurable. However, you, me, not your young sister must understand that fn get_temp_from_any_sensor_static1_1(t: &TempSensor01) {...} and fn get_temp_from_any_sensor_static1_2(t: &TempSensor02) {...} are two different functions that has nothing to do one with the other. Indeed, their signatures are completly different. One has a paramater of type &TempSensor01 while the other has a parameter of type &TempSensor02. Again, 2 totally different signatures and so 2 totally different methods.

I see get_temp_from_any_sensor_static2() function calls in main(). What is that? In fact when I write fn get_temp_from_any_sensor_static1(t: &impl Measurable) {...}, the keyword impl is a syntactic sugar. We can use the generic way of doing and write fn get_temp_from_any_sensor_static2<T: Measurable>(t: &T) {...}

fn get_temp_from_any_sensor_static2<T: Measurable>(t: &T) {

println!("{}", t.get_temp());

}

Nothing sexy here. Before the list of parameters, we declare the trait T as Measurable (do you see the <T: Measurable>?). At the end of the day the monomorphized code is similar to the previous one. However this syntax allow us to define functions with multiple traits : fn get_temp_from_any_sensor_static3<T: Measurable + Identifiable>(sensor: &T) {...}. We will use this syntax in the Multiple Traits section later.

Optional - Because the evil is in the details

Copy and paste the code fragment below in Rust Playground

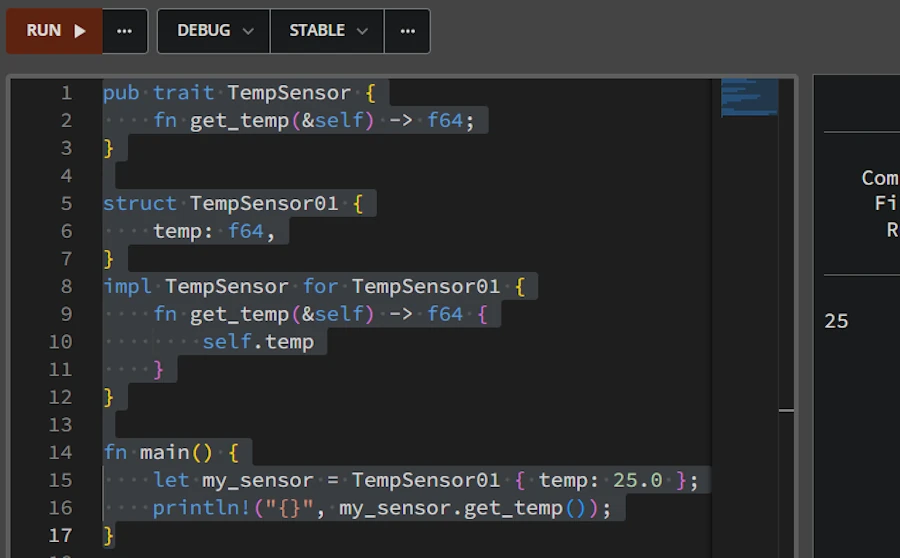

pub trait TempSensor {

fn get_temp(&self) -> f64;

}

struct TempSensor01 {

temp: f64,

}

impl TempSensor for TempSensor01 {

fn get_temp(&self) -> f64 {

self.temp

}

}

fn main() {

let my_sensor = TempSensor01 { temp: 25.0 };

println!("{}", my_sensor.get_temp());

}

Do you fully understand what happens here?

1.On the side of the trait TempSensor

pub trait TempSensor {

fn get_temp(&self) -> f64;

}

- I don’t want

selfas a parameter becauseget_temp()would take ownership of the object on whichget_temp()is called. - Then the caller would not be able to use the object afterwards.

- That would be silly. It is much better to expect a

&selfas a first parameter.

2. On the side of the caller main()

println!("{}", my_sensor.get_temp());

- Because the method’s receiver (see

fn get_temp(&self) -> f64 {...}) expect&selfas a first parameter, the call site needs a shared borrow as a first argument. - Rust’s method-call sugar applies auto-borrow (and auto-deref when needed), so we don’t have to write the

&ourself. my_sensor.get_temp()is “desugared” to something like :

println!("{}", <TempSensor01 as TempSensor>::get_temp(&my_sensor));

Do you see the & in front of my_sensor in ::get_temp(&my_sensor)? <TempSensor01 as TempSensor>::get_temp(&my_sensor) is called the UFCS (Uniform Function Call Syntax) form.

Again, if the normal method call is :

let my_sensor = TempSensor01 { temp: 25.0 };

println!("{}", my_sensor.get_temp());

Then the UFCS form (desugared equivalent) is:

println!("{}", TempSensor::get_temp(&my_sensor));

And if there could be ambiguity (multiple traits with get_temp() for example), it can be disambiguate with the concrete type:

println!("{}", <TempSensor01 as TempSensor>::get_temp(&my_sensor));

3. Two questions, just to make sure

1. In Rust Playground, what happens if you modify main() as below?

fn main() {

let my_sensor = TempSensor01 { temp: 25.0 };

println!("{}", &my_sensor.get_temp());

}

It works apparently and 25 is printed. We can imagine that we helped the compiler, showing that we know the call is desugared as: <TempSensor01 as TempSensor>::get_temp(&my_sensor). But NO. In fact, due to precedence of the operators, instead it means something like “call get_temp(), then take a reference to the return value”. In other words: & (my_sensor.get_temp()) which is a &f64.

2. In Rust Playground, what happens if you modify main() as below?

fn main() {

let my_sensor = TempSensor01 { temp: 25.0 };

println!("{}", (&my_sensor).get_temp());

}

It works, 25 is printed and it corresponds to our intend. Indeed (&my_sensor) is an explicit borrow of my_sensor. The method .get_temp(&self) expects &self, so the types match perfectly. However, it’s redundant and unnecessary because the compiler would have inserted the & automatically in my_sensor.get_temp().

At this point we should have everything we need to understand this first sample code. Read it, read it again. Run it, modify it. Break it. Make it run again. I can’t do it for you.

Exercise

- Add a

get_label()method to theMeasurabletrait - Implement it for

TempSensor01andTempSensor02 - Use it in

get_temp_from_any_sensor_static1to display the label (if any) - Copy and paste the code below in Rust Playground. Make sure you understand each line

pub trait TempSensor {

fn get_temp(&self) -> f64;

}

struct TempSensor01 {

temp: f64,

}

impl TempSensor for TempSensor01 {

fn get_temp(&self) -> f64 {

self.temp

}

}

fn main() {

let my_sensor = TempSensor01 { temp: 25.0 };

let t1 = my_sensor.get_temp(); // auto-borrow

let t2 = (&my_sensor).get_temp(); // explicit borrow

let t3 = TempSensor::get_temp(&my_sensor); // UFCS form

let t4 = <TempSensor01 as TempSensor>::get_temp(&my_sensor); // fully explicit UFCS

println!("{} {} {} {}", t1, t2, t3, t4);

}

Summary

- We have 2 types of temperature sensor

- We define a trait Measurable

- Kind of contract/interface with a set of methods, functions, variables to be implemented

- We implement the method of the trait for the data type of interest

- We can define a function that take as parameter any variable with the trait Measurable

- We can either use the

implkeyword or the generic syntax

- We can either use the

- So far everything is known at compile time. There is no impact at runtime.

Dynamic Dispatch

Where the data types are discovered at runtime.

Running the demo code

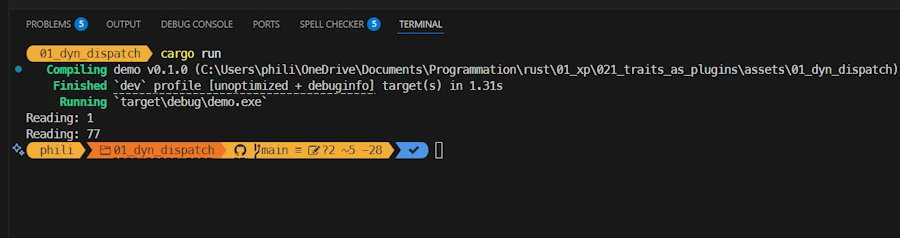

- Right click on

assets/01_dyn_dispatch - Select the option “Open in Integrated Terminal”

cargo run

Explanations 1/2

In the previous sample code everything is fine but everything is known at compile time. This means that when we arrive in Munich at the factory, once the sensors are deployed, we open the source code, we list all the sensors, we compile and run the new version of the monitoring system… This is simply not scalable. Among others because this is not maintenable (we will end up with a custom version per plant).

What we need is a way to dynamically call the right version of get_temp(). What we want to write is something like: println!("Reading: {}", s.get_temp()); no matter if s is a sensor of type TempSensor1 or TempSensor2.

This is where dynamic dispatch comes in.

Show me the code!

trait Measurable {

fn get_temp(&self) -> f64;

}

struct TempSensor01 {

temp: f64,

}

impl Measurable for TempSensor01 {

fn get_temp(&self) -> f64 {

self.temp

}

}

#[allow(dead_code)]

struct TempSensor02 {

label: String,

temp: f64,

}

impl Measurable for TempSensor02 {

fn get_temp(&self) -> f64 {

self.temp * 9.0 / 5.0 + 32.0

}

}

fn make_sensor(kind: &str) -> Box<dyn Measurable> {

match kind {

"celsius" => Box::new(TempSensor01 { temp: 1.0 }),

"fahrenheit" => Box::new(TempSensor02 {

label: "thermocouple".into(),

temp: 25.0, // 77 °F

}),

_ => Box::new(TempSensor01 { temp: 0.0 }),

}

}

fn main() {

let mut sensors: Vec<Box<dyn Measurable>> = Vec::new();

sensors.push(make_sensor("celsius"));

sensors.push(make_sensor("fahrenheit"));

for s in &sensors {

println!("Reading: {}", s.get_temp());

}

}

Explanations 2/2

The beginning of the code is exactly the same. We define the Measurable trait as before. Then we create the 2 temperature sensors and we implement get_temp() for each of them. Nothing new under the sun.

trait Measurable {

fn get_temp(&self) -> f64;

}

struct TempSensor01 {

temp: f64,

}

impl Measurable for TempSensor01 {

fn get_temp(&self) -> f64 {

self.temp

}

}

struct TempSensor02 {

label: String,

temp: f64,

}

impl Measurable for TempSensor02 {

fn get_temp(&self) -> f64 {

self.temp * 9.0 / 5.0 + 32.0

}

}

Now, the changes are in the main() function. First we create a vector of Measurable stuff. However, since Measurable is not a data type, the statement looks like this : let mut sensors: Vec<Box<dyn Measurable>> = Vec::new();. In plain English this says something like :

- Create a mutable vector (

sensorswith an ‘s’) of boxed trait objects implementingMeasurable. Boxputs each object on the heap, ensuring a fixed-size pointer is stored in the vector.- The

dynkeyword indicates dynamic dispatch, meaning the specific method to call is determined at runtime based on the actual type inside the box.

fn main() {

let mut sensors: Vec<Box<dyn Measurable>> = Vec::new();

sensors.push(make_sensor("celsius"));

sensors.push(make_sensor("fahrenheit"));

for s in &sensors {

println!("Reading: {}", s.get_temp());

}

}

Once the vector sensors is created, in the for loop we can invoke the get_temp() method on each element of the vector. The appropriate version of get_temp() is called. It does not come for free however. Behind the scene, at runtime, the code uses what is called a fat pointer. This pointer includes a pointer pointing to the data and a second pointer pointing to a table on the heap. In the table (vtable), there is a pointer pointing to the memory address were the get_temp() method is located.

In the first sample code we had direct calls because everything was known at compile time. Here we point to a table, then we find in the table the address of get_temp() and then we invoke it. We get much more flexibility but, again, it comes with a cost at runtime. Please don’t start grumbling, don’t assume but run benchmarks if you suspect the dynamic dispatch is killing your application.

What is the make_sensor() function call I can see above? sensors is a vector of boxed trait objects implementing Measurable. In this context make_sensor() is a kind of factory that creates 2 different flavors of sensor based on the argument (celcius or the other, the He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named). Here is the code of make_sensor() :

fn make_sensor(kind: &str) -> Box<dyn Measurable> {

match kind {

"celsius" => Box::new(TempSensor01 { temp: 1.0 }),

"fahrenheit" => Box::new(TempSensor02 {

label: "thermocouple".into(),

temp: 25.0, // 77 °F

}),

_ => Box::new(TempSensor01 { temp: 0.0 }),

}

}

Using a match expression, based on kind, it returns either a box containing a pointer to a TempSensor01 or to a TempSensor02. The code is as simple as possible. All sensors of the same type hold the same temperature but this is not the point here.

In the signature of the function (fn make_sensor(kind: &str) -> Box<dyn Measurable>) we use de dyn keyword to mark the dynamic dispatch while in the body we “simply” return a Box::new(TempSensor01 OR TempSensor02).

Again what really matters is the for loop in the main() function. Indeed it shows how to invoque the same method on every object of the vector because they implement the Measurable trait.

for s in &sensors {

println!("Reading: {}", s.get_temp());

}

Exercise

- In

main(), add a linesensors.push(make_sensor("kelvin"));and make it work - Can you explain the difference between

callandinvoketo your little sister? - Can you explain the difference between

expressionandstatementto your beloved grandma?

Summary

- As before, 2 types of temperature sensor with a trait

Measurable - Thanks to dynamic dispatch we can invoque

.get_temp()no matter the kind of sensor - The vector definition is :

let mut sensors: Vec<Box<dyn Measurable>> = Vec::new(); - The factory returns

Box<dyn Measurable>(exempli gratiaBox::new(TempSensor01 { temp: 1.0 }))

Default Implementation

When a data type cannot yet implement a method from the trait (interface)

Running the demo code

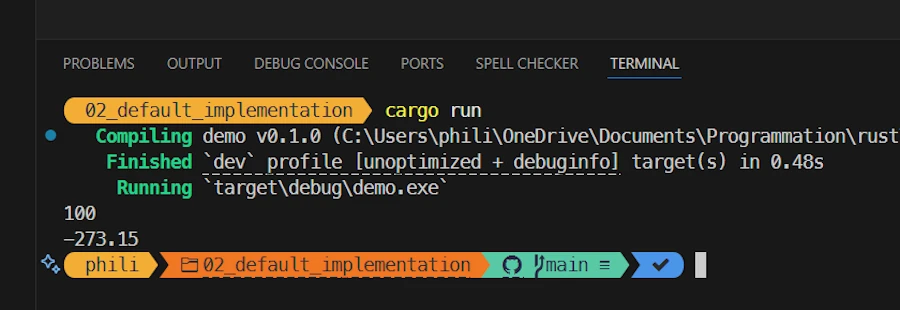

- Right click on

assets/02_default_implementation - Select the option “Open in Integrated Terminal”

cargo run

Explanations 1/2

We arrive in Paris, but — as you can imagine — the team responsible for deploying and calibrating the sensors is still on strike (welcome to France 😁). We’re leaving tomorrow, the customer doesn’t want to cover extra hotel nights or flight changes, and we still need to prove that our software works end-to-end if we want to get paid.

This is exactly where a default implementation comes to the rescue. It lets us demonstrate a fully functional system, even if some sensors aren’t providing real measurements yet. Let’s see how.

Show me the code!

pub trait Measurable {

fn get_temp(&self) -> f64 {

-273.15

}

}

struct TempSensor01 {

temp: f64,

}

impl Measurable for TempSensor01 {

fn get_temp(&self) -> f64 {

self.temp

}

}

struct TempSensor02 {

label: String,

temp: f64,

}

impl Measurable for TempSensor02 {}

fn main() {

let sensor100 = TempSensor01 { temp: 100.0 };

println!("{}", sensor100.get_temp());

let sensor200 = TempSensor02 {

label: "thermocouple".into(),

temp: 200.0,

};

println!("{}", sensor200.get_temp());

}

Explanations 2/2

By now you should know the story. 2 temperature sensors define 2 different data types and a trait Measurable propose an interface.

What is new here, is that the trait proposes a default implementation for the get_temp() method.

pub trait Measurable {

fn get_temp(&self) -> f64 {

-273.15

}

}

It says something like : if a data type wants to have the Measurable trait but is not yet able to define the get_temp() method, don’t worry, be happy, I will provide a default version for free.

And this is exactly what happens with TempSensor02 with the line :

impl Measurable for TempSensor02 {}

Note that the body is empty. Do you see the {}? The get_temp() is simply not yet defined for TempSensor02. When the monomorphization takes place, the default implementation will be used instead. This is what we can see in the terminal.

- When

println!("{}", sensor100.get_temp());is executed the value100is displayed - When the line

println!("{}", sensor200.get_temp());is executed the value-273.15is displayed while one could have expected200.

We should also keep in mind that it’s not all or nothing. Read the code below. Try to anticipate the outputs. Copy/paste and run the code below in the Rust Playground (I can’t do it for you honey).

pub trait Measurable {

fn get_temp(&self) -> f64 {

-273.15

}

fn get_label(&self) -> String {

"No Label".into()

}

}

struct TempSensor01 {

temp: f64,

}

impl Measurable for TempSensor01 {

fn get_temp(&self) -> f64 {

self.temp

}

// `get_label` is not implemented

}

#[allow(dead_code)]

struct TempSensor02 {

label: String,

temp: f64,

}

impl Measurable for TempSensor02 {

// `get_temp` is not implemented

fn get_label(&self) -> String {

self.label.clone().into()

}

}

fn main() {

let sensor100 = TempSensor01 { temp: 100.0 };

let sensor200 = TempSensor02 { label: "thermocouple".into(), temp: 200.0 };

println!("{}°C, label: {}", sensor100.get_temp(), sensor100.get_label());

println!("{}°C, label: {}", sensor200.get_temp(), sensor200.get_label());

}

Now, when your tears of joy have dried, step back and take the time to realize how flexible the “default implementation” option is. For example think about a Measurable trait in a lib. The consumers of the lib can use it immediately. The values they obtain may seem strange at first, but at least they can develop the software component they are in charge of. Later, when you are able to replace the default implementation with the real implementation, nothing will change from their point of view. API users will simply obtain more realistic values.

Exercise

- Add

get_label()method with default implementation toMeasurable - Call it on

sensor100andsensor200inmain()

Summary

- A trait can propose default implementations for its methods

- Data type willing to implement the trait can cherry pick the methods they want to define

- This is not all or nothing and you can have much more than 52 shades of grey

- From the consumer of the interface everything seems OK.