Option<T> in Rust: 15 Examples from Beginner to Advanced

A Code-First Guide with Runnable Examples

TL;DR

-

A function (or a method) that doesn’t always have a meaningful value to return should return an

Option<T>. Respectively astructwhose fields may be empty should be of typeOption<T>.// Example 01: `Option<T>` as a Return Value fn get_selection(&self) -> Option<String> { Some("lorem ipsum".to_string()) // None } -

If the pattern

Some(my_txt)successfully matches theOption<T>returned bymy_editor.get_selection(), then bind its contents tomy_txtand run the first block; otherwise, run theelseblock.// Example 02: Conditional Pattern Matching if let Some(my_txt) = my_editor.get_selection() { println!("Selection: {my_txt}"); } else { println!("No text selected"); } -

Match on

&editor.path_to_file. If it contains a value, bind a reference to that value topath, then call the methodfile_name()onpathand bind the result tomy_file_name. IfNone, return early.”// Example 03: `match` Expression with Early Return let my_file_name = match &editor.path_to_file { Some(path) => path.file_name(), None => return, }; -

Let the pattern

Some(my_path)match on&editor.path_to_file. If it doesn’t match (i.e., it’sNone), execute theelseblock which returns early.// Example 04: "Modern" Early Return let Some(my_path) = &editor.path_to_file else { return; };

This is Episode 00

The Posts Of The Saga

- 🟢 Episode 00: Intro + Beginner Examples

- 🔵 Episode 01: Intermediate Examples

- 🔴 Episode 02: Advanced Examples + Advises + Cheat Sheet…

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- How to Use This Guide?

- Learning from existing code

- 🟢 - Example 01 -

Option<T>as a Return Value - 🟢 - Example 02 - Conditional Pattern Matching -

if let Some(v) = Option<T> - 🟢 - Example 03 -

matchExpression with Early Return - 🟢 - Example 04 - “Modern” Early Return -

let...else

Introduction

Personally, while still learning Rust I always struggle with the Some(v) syntax. I can read and understand most of the code I get, but the next day when I need to write a line of code to handle an Option<T> I don’t feel comfortable. I’ve been dealing with this problem since the beginning and I can’t seem to get rid of it. What’s worse, I can understand code written by others or code generated by Claude/ChatGPT, but I can’t write it myself with ease.

In short, this post is a kind of therapy during which I will try to heal myself 😁.

How to Use This Guide?

I want to try something new here so this article uses a sort of inverted pedagogy: code first, explanation second and cherry on the cake… You don’t have to read it all all at once since the post is split in 3 different levels:

- 🟢 Beginner: Basic examples (

if let,match) - 🔵 Intermediate: Combinators and chaining (

map,and_then,?) - 🔴 Advanced: Ownership tricks (

as_ref,take,flatten)

Each Example section is organized as follow:

- Real-world context: Few words about the context before we look at the code

- Runnable Example:

- Copy the code

- Paste it into Rust Playground

- Press Ctrl+E (or click “Run”)

- Experiment by modifying the code. Break everything, spend some time in the Playground. Play!

- Read it Aloud: This section is MUCH MORE IMPORTANT than you may think in first approximation. Indeed, I’m convinced that too often, in programming (like in Maths) we look at the code (at the formula) but we don’t read the code (nor the formula). However the code tells us a story and this is this story that I try to tell in the section.

- Comments: my comments about the code, my understanding or some other stuff I may have in mind.

- Key Points: what to keep in mind.

- Find More Examples: don’t trust me. Check by yourself. Search in the code of largely used crates, not in ad hoc projects nor in toy projects (see below how to)

Learning from existing code

The idea is to learn from others and to “see” how do they do. I propose to clone the projects below. Copy the block below from cd to 4-rust and paste it in your terminal. And, yes, you can copy more than one line at a time in Powershell.

cd $env:TMP

git clone https://github.com/BurntSushi/ripgrep

git clone https://github.com/microsoft/edit

git clone https://github.com/sharkdp/hexyl

git clone https://github.com/ajeetdsouza/zoxide

git clone https://github.com/aovestdipaperino/turbo-vision-4-rust

Other crates include but are not limited to : bat, fd, tokei, hyperfine… Stay away from projects that are either too large or too complex. Don’t worry, we will not build or install these projects (for example edit require the nightly build Rust compiler), we will only search in their code base.

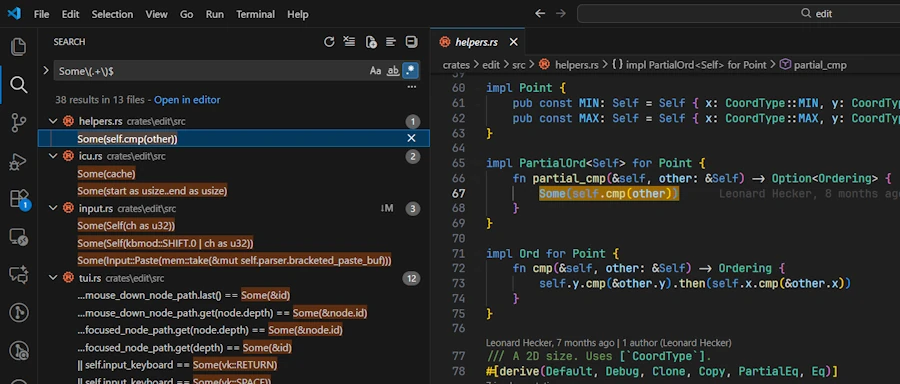

Later in this post, at the end of each Example, I will share the regular expression to use to find the lines of code corresponding to the example. Once you have this regular expression in hands (let’s say Some\(.+\)$) you can either:

In VSCode:

- Open the project of interest

CTRL+SHIFT+F, enable regex (ALT+R), type:Some\(.+\)$

In Powershell: copy’n paste the line below in a terminal.

Get-ChildItem -Path "$env:TMP/hexyl/src" -Filter *.rs -Recurse |

ForEach-Object {

# Read file content with line numbers

Select-String -Path $_.FullName -Pattern 'Some\(.+\)$' -SimpleMatch:$false |

ForEach-Object {

# Output file path and line number

[PSCustomObject]@{

File = $_.Path

LineNumber = $_.LineNumber

LineText = $_.Line.Trim()

}

}

}

Above we look into the codebase of hexyl. This work the same way for zoxyde/src or turbo-vision-4-rust/src.

In the case of:

edituse the path:$env:TMP/edit/crates/edit/srcripgrepuse the path:$env:TMP/ripgrep/crates

Based on what I saw, it seems ripgrep is the project that cover most if not all the examples of this post. I strongly recommend you open it now in you favorite IDE. This said… Let’s dive in!

🟢 - Example 01 - Option<T> as a Return Value

Real-world context

I want to start with this use case because, for me, this is, by far, the easiest. Indeed, we can easily explain in plain English that a function might search for a file and, if it can’t find it, simply returns “nothing”. If it succeeds, it returns something—like the first line of the file. Using Option<T> makes sense for any function that might not succeed (without throwing an error or crashing) but also doesn’t always have a meaningful value to return. This pattern is common for operations like searching, parsing, or handling optional configuration.

On the other hand it is not too complicated to imagine a struct where some of its fields may, at one point, contain nothing. Think about an editor with no file loaded (see Example 02 and Code snippet 04). In this cas it really make sense to give to these field a type Option<T>.

Easy to explain, easy to translate. The easiest, I told you.

Runnable Example

Copy and paste in Rust Playground

struct Editor {

}

impl Editor {

fn get_selection(&self) -> Option<String> {

// Simulate selection: uncomment one to test both cases

Some("lorem ipsum".to_string())

// None

}

}

fn main() {

let my_editor = Editor {};

let selection = my_editor.get_selection();

if selection.is_some(){

println!("Selection: {}", selection.unwrap());

}else{

println!("No text selected");

}

}

Read it Aloud

In main(), the code says : “get_selection() returns an Option<String> which contains the selected text as a String or None. The if selection.is_some() checks if the return value contains something and if so, executes the first block. Otherwise, it executes the else branch.”

Comments

- It is important to realize that

get_selection()returns a typeOption<String>NOT a typeString - In the playground, replace

Some("lorem ipsum".to_string())withSome("lorem ipsum".into()). Does it work? Why? - Do you agree on the fact that

selection.is_some()does NOT extract the value from theOption<T>but just check if there is a value in theOption<T>? - Take your time and read the documentation and don’t forget to click the link Module Level Documentation and read the page.

- Is it clear that once we checked the

Option<T>contains something thenunwrap()extract this thing? - Duplicate the

println!("Selection: {}", selection.unwrap());at the very end ofmain(). Does it works? Why?

Key Points

- Pattern: The function returns an

Option<T>(hereOption<String>). It can beNoneorSome(v). - When to use: When we need to express the fact that a function or a method can return nothing or something.

- Usage: When a struct, an application, a function has an optional parameter or return value,

Option<T>should be used.

Find More Examples

- Regular expression to use either in VSCode ou Powershell:

Some\(.+\)$ - Make the test. Now! Open

editproject in VSCode and search forSome\(.+\)$(CTRL+SHIFT+FthenAlt+R).

🟢 - Example 02 - Conditional Pattern Matching - if let Some(v) = Option<T>

Real-world context

Updating configuration, processing optional user input, conditional initialization.

Runnable Examples

Code snippet 00

Copy and paste in Rust Playground. In the first three versions of the earlier code, within main(), we review several alternative approaches before using the if let Some(...) = Option<T> pattern.

struct Editor {

}

impl Editor {

fn get_selection(&self) -> Option<String> {

// Simulate selection: uncomment one to test both cases

Some("lorem ipsum".into())

// None

}

}

fn main() {

let my_editor = Editor {};

let msg = my_editor.get_selection();

match msg {

Some(my_txt) => println!("Selection: {my_txt}"),

None => println!("No text selected")

};

}

Code snippet 01

struct Editor {

}

impl Editor {

fn get_selection(&self) -> Option<String> {

// Simulate selection: uncomment one to test both cases

Some("lorem ipsum".into())

// None

}

}

fn main() {

let my_editor = Editor {};

match my_editor.get_selection() {

Some(my_txt) => println!("Selection: {my_txt}"),

None => println!("No text selected")

}

}

Code snippet 02

struct Editor {

}

impl Editor {

fn get_selection(&self) -> Option<String> {

// Simulate selection: uncomment one to test both cases

Some("lorem ipsum".into())

// None

}

}

fn main() {

let my_editor = Editor {};

let msg = match my_editor.get_selection() {

Some(my_txt) => format!("Selection: {my_txt}"),

None => format!("No text selected")

};

println!("{msg}");

}

Code snippet 03

Copy and paste in Rust Playground. In this version of the previous code we use if let Some() pattern.

struct Editor {

}

impl Editor {

fn get_selection(&self) -> Option<String> {

// Simulate selection: uncomment one to test both cases

Some("lorem ipsum".into())

// None

}

}

fn main() {

let my_editor = Editor {};

// The `if let Some(...) = Option<T>` conditional pattern matching

// => unwrap and use the selection only if Some()

if let Some(my_txt) = my_editor.get_selection() {

println!("Selection: {my_txt}");

} else {

println!("No text selected");

}

}

Code snippet 04

Copy and paste in Rust Playground

use std::path::PathBuf;

struct Editor {

path_to_file: Option<PathBuf>,

}

impl Editor {

fn set_path(&mut self, path: PathBuf) {

self.path_to_file = Some(path);

}

}

fn main() {

let mut my_editor = Editor { path_to_file: None };

// Uncomment one to test both cases

let new_path = Some(PathBuf::from(r"tmp/my_file.txt"));

// let new_path = None;

if let Some(path) = new_path {

my_editor.set_path(path);

}

println!("The file: {:?}", my_editor.path_to_file);

}

Read it Aloud

Code snippet 00: The code says: “In main(), msg is an Option<String> and we use a match expression to cover explicitly all the possible values returned by my_editor.get_selection().”

Code snippet 01: The code says: “In main(), on the return of my_editor.get_selection() we use a match expression to cover explicitly all the possible values.”

Code snippet 02: Here the code tells us this story: “The result of the match expression is used to initialize the msg variable which receive a formatted string before to be printed.”

Code snippet 03: Here the plot unfolds as follows: “If the pattern Some(my_txt) successfully matches the Option<T> returned by my_editor.get_selection(), then bind its contents to my_txt and run the first block; otherwise, run the else block.”

Code snippet 04:

- Here is the context of the story

- The

Editormay have a path to a file (or not). This explains why the fieldpath_to_fileis of typeOption<PathBuf>. - When created,

my_editordoes not point to any particular file (see thepath_to_file: None). - Then a

new_pathvariable is created. It is anOption<PathBuf>containing a path to a file.

- The

That being said, the story goes like this: “If new_path contains a value, bind it to path and call the method set_path() with it as an argument. Otherwise, skip the block entirely.”

Comments

- Code snippet 03.

if let Some(x) = expressionis NOT a boolean expression. This is a conditional pattern matching. Rust try to match the patternSome(...)with the value on the right. If the match succeeds, theifblock is executed; otherwise, it is ignored.- Personally, that’s what trips me up every time because I can’t help reading it as a Boolean expression.

- Code snippet 03.

if let Some(x) = expressionis NOT a boolean expression, see it is as a shortened version of amatch. - Code snippet 03. When we read a line like

if let Some(...) = Option<T>{...}we should say “If the patternSome(...)successfully matches theOption<T>then blah blah blah…” - Code snippet 02.

matchis an expression. It evaluates to a single value. Look, there is a;at the end of the linelet msg = ... - Code snippet 02. Do you see the difference between the second and third code snippet? In the latter,

msgreceive the result offormat!and then it is printed. Againmatchis an expression, NOT a statement. - Code snippet 04. Uncomment the line

let new_path = None;(comment the line above). Is the behavior of the code crystal clear? - Code snippet 04. Add this line

println!("{}", new_path.is_some());at the very end of the code. What happens? Why?. - Each time one of our data type have a field which may contain something or nothing we should use an

Option<T>. See Example 01.

Key Points

- Pattern:

if let Some(x) = expressionis NOT a boolean expression, it is a conditional pattern matching - Storytelling: If the pattern

Some(x)successfully matches theOption<T>then bind its contents toxand run the first block; otherwise, run theelseblock.” - Pattern: Conditionally execute code only when

Option<T>has a value - Ownership: As with the

.unwrap()(see Example 01), if the patternSome(x)matches theOption<T>then the value inside theOption<T>is moved intox

Find More Examples

Regular expression to use either in VSCode ou Powershell: if let Some\(.+\) =

🟢 - Example 03 - match Expression with Early Return

Real-world context

Anything that might fail and requires early exit: File operations, network requests, database queries…

Runnable Example

Copy and paste in Rust Playground

use std::path::PathBuf;

struct Editor {

path_to_file: Option<PathBuf>,

}

fn save_file(editor: &Editor) {

let my_file_name = match &editor.path_to_file {

Some(path) => path.file_name(),

None => return,

};

if let Some(name) = my_file_name {

println!("Saving file: {:?}", name);

}

}

fn main() {

let editor = Editor {

// Uncomment one to test both cases

path_to_file: Some(PathBuf::from(r"tmp/my_file.txt")),

// path_to_file: None,

};

save_file(&editor);

}

Read it Aloud

- In

save_file()the code says: “Match on&editor.path_to_file. If it contains a value, bind a reference to that value topath, then call the methodfile_name()onpathand bind the result tomy_file_name. IfNone, return early.”

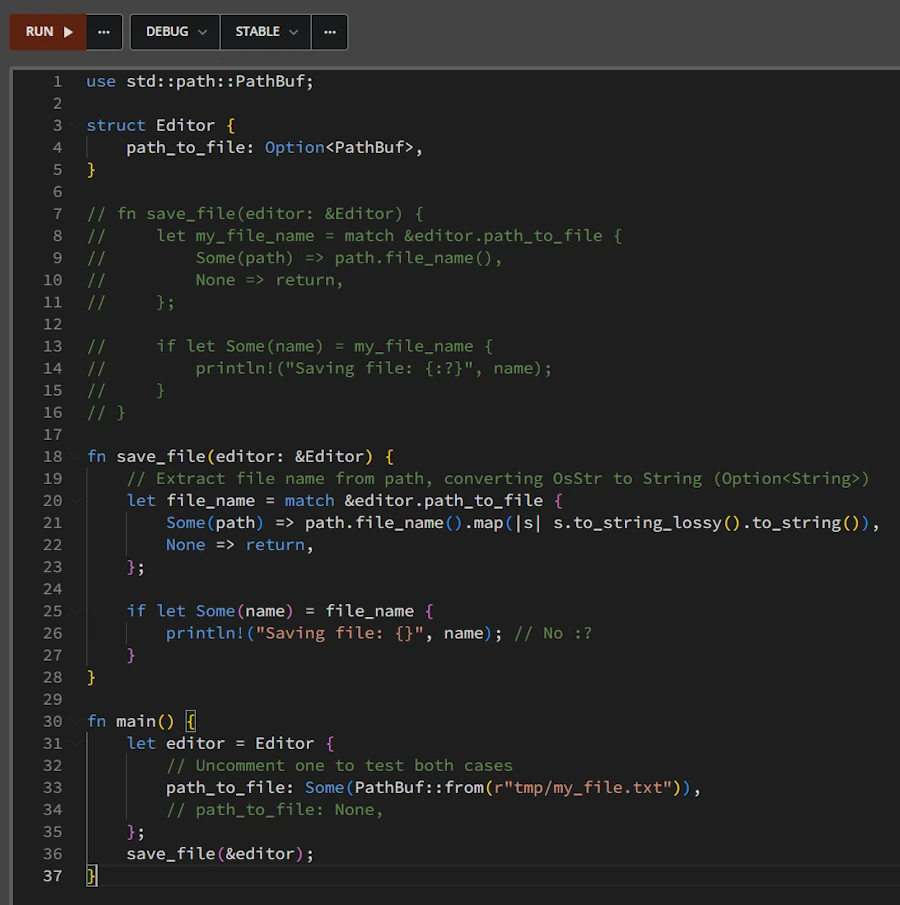

Comments

save_file()has a reference to the Editor as a parameter (borrow)- In the Playground, remove the reference in front of

&editor.path_to_file. What happens? Why? - It is important to understand that we don’t directly “bind” the file name, we bind the result of the extraction, which is itself an

Option<T>(because a path might not have a file name, for example/or.). -

Ideally we should write

save_file()as below:fn save_file(editor: &Editor) { // Extract file name from path, converting OsStr to String (Option<String>) let file_name = match &editor.path_to_file { Some(path) => path.file_name().map(|s| s.to_string_lossy().to_string()), None => return, }; if let Some(name) = file_name { println!("Saving file: {}", name); // No :? } } - At the end of

main()add the 2 lines below. What do we need to do to compile. Why?editor.path_to_file = Some(PathBuf::from(r"tmp/my_file2.txt")); save_file(&editor);

Key Points

- Pattern:

matchwith early return avoids deep nesting - When to use: When

Nonemeans “abort this operation” - Modern alternative: See next example with

let...else

Find More Examples

Regular expression to use either in VSCode ou Powershell: match .+ \{\s*Some\(.+\) => .+,\s*None => return

🟢 - Example 04 - “Modern” Early Return - let...else

Real-world context

Same as match early return, but more concise.

Runnable Example

Copy and paste in Rust Playground

use std::path::PathBuf;

struct Editor {

path_to_file: Option<PathBuf>,

}

fn save_file(editor: &Editor) {

let Some(my_path) = &editor.path_to_file else {

eprintln!("No path to file available");

return;

};

if let Some(name) = my_path

.file_name()

.map(|s| s.to_string_lossy().to_string())

{

println!("Saving file: {}", name);

}

}

fn main() {

let mut editor = Editor {

// Uncomment one to test both cases

// path_to_file: Some(PathBuf::from(r"tmp/my_file.txt")),

path_to_file: None,

};

save_file(&editor);

editor.path_to_file = Some(PathBuf::from(r"tmp/my_file2.txt"));

save_file(&editor);

}

Read it Aloud

- At the begining of

save_file()the code says: “Let the patternSome(my_path)match on&editor.path_to_file. If it doesn’t match (i.e., it’sNone), execute theelseblock which returns early.”

Comments

- Compare the end of

save_file()in Example 03 with Example 04. In the latter we extract file name from path, converting OsStr to String. It was mentioned in the comments of Example 03.

Key Points

- Pattern:

let Some(var) = expr else { ... }replaces match with early return - Readability: More concise than match when you only care about the

Nonecase - Requirement: The else block must diverge (return, break, continue, panic)

- Modern: Introduced in Rust 1.65 (2022) - idiomatic for new code

Find More Examples

Regular expression to use either in VSCode ou Powershell: let Some\(.+\) = .+ else. Try it with ripgrep for example.