Option<T> in Rust: 15 Examples from Beginner to Advanced

A Code-First Guide with Runnable Examples

TL;DR

-

as_ref()convertsOption<T>toOption<&T>, so that we can peek inside without consuming.as_mut()givesOption<&mut T>for peek and poke. Both leave the originalOption<T>intact.// Example 10: Borrowing Instead of Moving let len = path.as_ref().map(|p| p.as_os_str().len()); path.as_mut().map(|p| p.push("documents")); -

Give me the value inside

Some(v)+ replace theOption<T>withNone+ and return the value asOption<T>// Example 11: Extracting Value and Leaving `None` if let Some(_f) = self.file.take() {...} -

If

Option<T>isSome(v)and the condition is true, keep it asSome(v). Otherwise, returnNone. It’s likemap()but it can remove values.// Example 12: Conditional Mapping - .filter() let result = name.map(|n| n.trim()).filter(|n| !n.is_empty()).map(|n| n.to_uppercase()); -

.flatten()convertsVec<Option<T>>toVec<T>by discardingNonewhile.filter_map(|x| optional_transform(x))combines.map()and.flatten()in one step.// Example 13: Working with Collections of Options let out: Vec<i32> = in .iter() .filter_map(|&s| parse_number(s)) .collect(); -

Some(a? + b?)offers a concise early-return logic toOptions<T>2 or more options. If allOptions<T>areSome(v)the processing takes place, otherwise, if any isNone, early replyNone.// Example 14: Combining Multiple Options fn add_options(a: Option<i32>, b: Option<i32>) -> Option<i32> { Some(a? + b?) } -

.copied()duplicates the value insideOption<&T>to produceOption<T>(requires theCopytrait)..cloned()does the same but uses theClonetrait instead - works for non-Copy types likeString.// Example 15: Converting `Option<&T>` to `Option<T>`

This is Episode 02

The Posts Of The Saga

- 🟢 Episode 00: Intro + Beginner Examples

- 🔵 Episode 01: Intermediate Examples

- 🔴 Episode 02: Advanced Examples + Advises + Cheat Sheet…

Table of Contents

- 🔴 - Example 10 - Borrowing Instead of Moving -

.as_ref()and.as_mut() - 🔴 - Example 11 - Extracting Value and Leaving

None-.take() - 🔴 - Example 12 - Conditional Mapping -

.filter() - 🔴 - Example 13 - Working with Collections of Options -

.flatten()and.filter_map() - 🔴 - Example 14 - Combining Multiple Options

- 🔴 - Example 15 - Converting

Option<&T>toOption<T>-.copied()and.cloned() - Some Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

- Quick Reference & Cheat Sheet

- Webliography

🔴 - Example 10 - Borrowing Instead of Moving - .as_ref() and .as_mut()

Real-world context

Inspecting Option<T> without consuming it, modifying in-place, reusing Option<T> after checking.

Runnable Example

Copy and paste in Rust Playground

// cargo run --example 10ex

fn main() {

// i32 implements Copy, so Option<i32> also implements Copy

let opt = Some(42);

// Pattern matching copies opt instead of moving it

if let Some(n) = opt {

println!("{n}"); // n is copied from the Option

}

println!("{:?}", opt); // OK: opt was copied, not moved

println!();

// String does NOT implement Copy, so Option<String> does not implement Copy either

let opt = Some(String::from("hello"));

// Pattern matching moves opt and its inner String

if let Some(s) = opt {

// s is moved out of opt

println!("Length: {}", s.len());

}

// println!("{:?}", opt); // ERROR: opt was moved and cannot be used here

// Borrowing with as_ref => Option<T> remains usable afterwards

println!();

let opt = Some(String::from("hello"));

if let Some(s) = opt.as_ref() {

println!("Length: {}", s.len());

}

println!("{:?}", opt); // Ah, ha, ha, ha, stayin' alive, stayin' alive

println!();

// this express the same intention as `as_ref`

if let Some(my_str) = &opt {

println!("Length: {}", my_str.len());

}

println!("{:?}", opt); // Ah, ha, ha, ha, stayin' alive, stayin' alive

println!();

let mut path = Some(std::env::current_dir().expect("Cannot read current dir"));

// as_ref() is useful with map - read without consuming

let len = path.as_ref().map(|p| p.as_os_str().len());

println!("The path {:?} has a length of {:?}", path, len);

// as_mut is useful with map - modify in place

path.as_mut().map(|p| p.push("documents"));

path.as_mut().map(|p| p.push("top_secret"));

println!("The path is now: {:?}", path);

}

Read it Aloud

“as_ref() converts Option<T> to Option<&T>, so that we can peek inside without consuming. as_mut() gives Option<&mut T> for peek and poke. Both leave the original Option<T> intact.”

Comments

IMPORTANT

The

Option<T>is considered moved unless it implementsCopytrait, which only happens ifTimplementsCopy.

Review Example 02 now that you have that in mind.

- With the first

if let Some(n) = opt, theOption<T>on the right-hand side is copied andoptremains available.i32implements theCopytrait- so

Option<i32>also implements Copy - so using

optin a pattern match copies theOption<T>instead of moving it optremains valid.

- With the second

if let Some(s) = opt, theOption<T>on the right-hand side is moved, which meansoptis no longer available afterward.Option<String>does not implement theCopytrait- so

optis moved into theif let Some(s) - we cannot use

optafterward

This explains the need for tools to “read” and to “read/write” inside Option<T>

Option<T>.as_ref()provides an immutable reference to the value inside theOption<T>Option<T>.as_mut()provides a mutable reference to the value inside theOption<T>.- In both cases, the

Option<T>itself is not consumed, but any changes made through the mutable reference do modify the underlying value. - An alternative to

if let Some(s) = opt.as_ref() {...isif let Some(s) = &opt {... - The line

path.as_mut().map(|p| p.push("documents"));generates a warning. Do you know why? How can you simplify the code?

Key Points

- Signature:

as_ref(&self) -> Option<&T>,as_mut(&mut self) -> Option<&mut T> - When to use: Reading Option multiple times, modifying without replacing

- With map:

opt.as_ref().map(|val| ...)lets us transform without moving - Ownership: Original Option keeps ownership - crucial for reuse

Find More Examples

Regular expressions to use either in VSCode ou Powershell: \.as_ref\(\)\.map or \.as_mut\(\)

🔴 - Example 11 - Extracting Value and Leaving None - .take()

Real-world context

Consuming resources (files, connections), state machines, cleanup operations, RAII.

Runnable Example

Copy and paste in Rust Playground

use std::fs::{self, File};

struct Editor {

file: Option<File>,

}

impl Editor {

fn is_open(&self) -> bool {

self.file.is_some()

}

fn close(&mut self) {

if let Some(_f) = self.file.take() {

// _f is File, self.file is now None automatically

println!("Closing file");

// _f is dropped and the file is automatically closed at the end of the block

}

}

}

fn main() {

let mut editor = Editor {

file: Some(File::create("temp.txt").expect("Failed to create temp.txt")),

};

println!("Is open: {}", editor.is_open()); // true

editor.close();

println!("Is open: {}", editor.is_open()); // false

// Clean up: remove temp.txt if it exists

if fs::metadata("temp.txt").is_ok() {

fs::remove_file("temp.txt").expect("Failed to delete temp.txt");

println!("temp.txt deleted");

}

}

Copy and paste in Rust Playground. This example demonstrates how to implement RAII (resource acquisition is initialization) with the help of take() even if early release are allowed.

struct Resource {

name: String,

}

impl Resource {

fn new(name: &str) -> Self {

println!("\t[{}] Acquired", name);

Self {

name: name.to_string(),

}

}

}

impl Drop for Resource {

fn drop(&mut self) {

println!("\t[{}] Released", self.name);

}

}

struct Guard {

resource: Option<Resource>,

}

impl Guard {

fn new(name: &str) -> Self {

Self {

resource: Some(Resource::new(name)),

}

}

// Manually release before scope ends

fn release(&mut self) {

if let Some(r) = self.resource.take() {

println!("\t[{}] Early release", r.name);

} // r is dropped here

}

}

impl Drop for Guard {

fn drop(&mut self) {

if self.resource.is_some() {

println!("\tGuard dropped with resource still held");

}

// resource.take() not needed here - Option<T> drops automatically

}

}

fn main() {

println!("Example 1: Auto release at scope end");

{

let _guard = Guard::new("DB Connection");

println!("\tDoing some work...");

} // _guard dropped here, Resource released

println!("\nExample 2: Early release with take()");

{

let mut guard = Guard::new("File Handle");

println!("\tDoing work...");

guard.release(); // Release early via take()

println!("\tMore work after release...");

} // guard dropped, but resource already gone

}

Read it Aloud

Option<T>.take() says: “Give me the value inside Some(v) + replace the Option<T> with None + and return the value as Option<T>.”

Comments

Option<T>.take()is a move + automaticNoneassignment in one operation.- First example

- The code at the end of

main()is here to make sure the file is deleted if it exists.

- The code at the end of

- RAII

- The

Option<Resource> + take()pattern is idiomatic for managing resources that we may want to release manually while maintaining RAII safety.

- The

Key Points

- Signature:

take(&mut self) -> Option<T>- requires mutable reference - Atomic: Extracts value and sets to

Nonein one step (prevents use-after-move bugs) - Common use: Cleanup, state transitions, resource management

- vs moving:

if let Some(x) = opt.take()vsif let Some(x) = opt(latter moves entire Option)

Find More Examples

VSCode search: \.take\(\) (regex) Regular expression to use either in VSCode ou Powershell: \.take\(\)

🔴 - Example 12 - Conditional Mapping - .filter()

Real-world context

Validation, keeping only values that meet criteria, sanitization.

Runnable Example

Copy and paste in Rust Playground

fn main() {

let numbers = vec![Some(1), Some(15), Some(25), None, Some(5)];

// Filter keeps only Some(v) where the predicate is true

let filtered: Vec<Option<i32>> = numbers.iter().map(|opt| opt.filter(|&n| n > 10)).collect();

println!("Raw numbers: {:?}", numbers); // [Some(1), Some(15), Some(25), None, Some(5)]

println!("Filtered : {:?}", filtered); // [None, Some(15), Some(25), None, None]

// Combining with map

let name = Some(" Zoubida ");

let result = name

.map(|n| n.trim())

.filter(|n| !n.is_empty()) // Keep only if not empty after trim

.map(|n| n.to_uppercase());

println!("{:?}", result); // Some("ZOUBIDA")

// Filter out invalid values

let maybe_age = Some(-5);

let valid_age = maybe_age.filter(|&age| age >= 0 && age <= 150);

println!("{:?}", valid_age); // None (negative age rejected)

}

Read it Aloud

filter(|val| condition) says: “If Option<T> is Some(v) and the condition is true, keep it as Some(v). Otherwise, return None. It’s like map() but it can remove values.”

Comments

- At this point it is important to read the story that the signatures tell us. In VSCode if we hover over the word

.filterwe can read :

core::option::Option

impl<T> Option<T>

pub const fn filter<P>(self, predicate: P) -> Self

where

P: FnOnce(&T) -> bool + Destruct,

T: Destruct,

I know what you think but this is like riding under the rain on track. No one like that but… This is an investment with large ROI, especially the next week-end in Belgium where it rains 370 days/year. Ok… Above we learn that, on an Option<T>, the predicate P acts on &T (did you notice the P: FnOnce(&T)?). The predicate borrows the tested values it does’nt consume them.

And what about .map()? Let’s play the game and we read:

core::iter::traits::iterator::Iterator

pub trait Iterator

pub fn map<B, F>(self, f: F) -> Map<Self, F>

where

Self: Sized,

F: FnMut(Self::Item) -> B,

Now, just to make sure we know what we are talking about while talking about the first filter… Copy and paste in Rust Playground the code below:

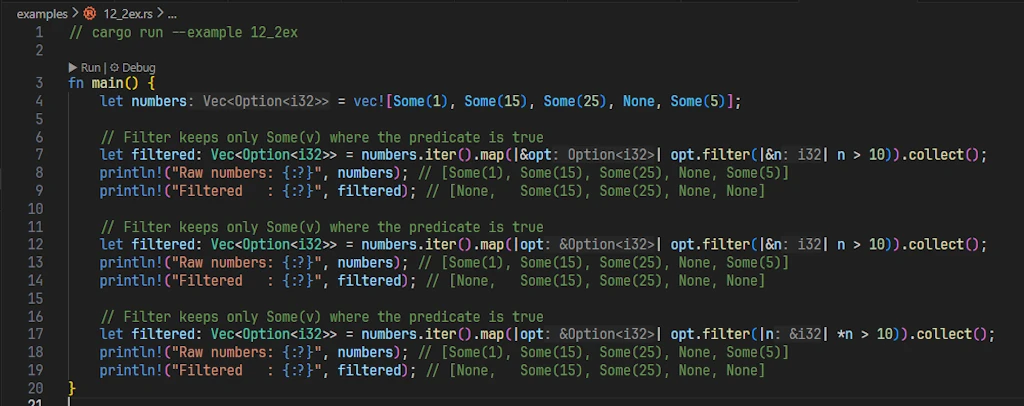

// cargo run --example 12_2ex

fn main() {

let numbers = vec![Some(1), Some(15), Some(25), None, Some(5)];

// Filter keeps only Some(v) where the predicate is true

let filtered: Vec<Option<i32>> = numbers.iter().map(|&opt| opt.filter(|&n| n > 10)).collect();

println!("Raw numbers: {:?}", numbers); // [Some(1), Some(15), Some(25), None, Some(5)]

println!("Filtered : {:?}", filtered); // [None, Some(15), Some(25), None, None]

// Filter keeps only Some(v) where the predicate is true

let filtered: Vec<Option<i32>> = numbers.iter().map(|opt| opt.filter(|&n| n > 10)).collect();

println!("Raw numbers: {:?}", numbers); // [Some(1), Some(15), Some(25), None, Some(5)]

println!("Filtered : {:?}", filtered); // [None, Some(15), Some(25), None, None]

// Filter keeps only Some(v) where the predicate is true

let filtered: Vec<Option<i32>> = numbers.iter().map(|opt| opt.filter(|n| *n > 10)).collect();

println!("Raw numbers: {:?}", numbers); // [Some(1), Some(15), Some(25), None, Some(5)]

println!("Filtered : {:?}", filtered); // [None, Some(15), Some(25), None, None]

}

If you use VSCode, feel free to press CTRL+ALT to reveal the types and you should see:

All three versions above compile and produce identical results, but they differ in how they handle references in the closure parameters. Let me break down each one:

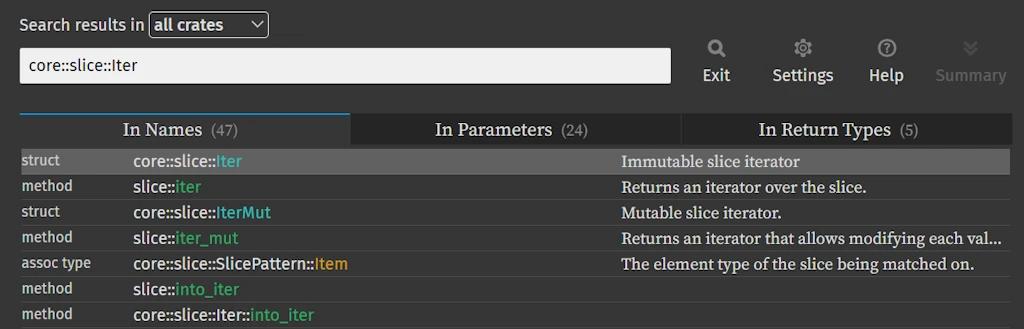

They all start with numbers.iter(). Reading the help of .iter() we learn the following:

core::slice

impl<T> [T]

pub const fn iter(&self) -> Iter<'_, T>

T = Option<i32>

- Note that rust-analyzer is smart enough to recall us that in our case,

T = Option<i32>. - We should also note that even if we call

.iter()on a vector, the documentation explains that it will be considered as a slice ([T]). - The return type is

Iter<'_, T>. The first element is a lifetime specifier. It indicates that the iterator is “bound” to the lifetime of the object on which we calliter()(here,numbers, the vector/slide ofOption<T>). Indeed, slice iterators borrow elements instead of moving them.

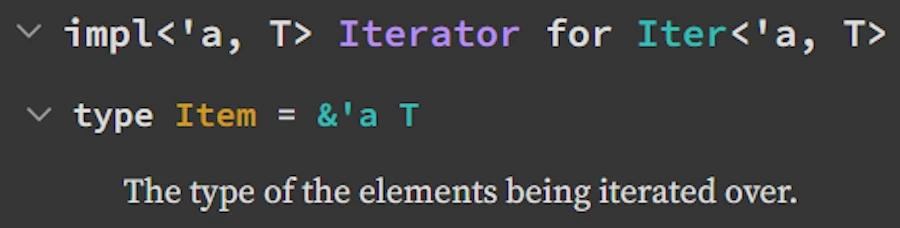

So at this point we know we will get a core::slice::Iter<'_, T> but what is precisely the returned type? We have to go on the Rust documentation and look for the struct core::slice::Iter

Once on the page of the Struct Iter, in the section Trait Implementations we look, in alphabetical order, for the implementation of the Iterator trait:

This is where we learn that the implementation define an associated type Item: type Item = &'a T. This means that the iterator of a slice of elements of type T produces references (&) to these elements, with the same lifetime ('a) as the iterator itself. To make a long story short, the iterator produces &Option<i32>

Now let’s analyze the 3 different versions of the line:

Version 1: |&opt| opt.filter(|&n| n > 10)

- Here we destructure the reference in the closure parameter. Since

numbers.iter()yields&Option<i32>, using|&opt|gives usopt: Option<i32>(a copy, sincei32isCopy). Then|&n|destructures the&i32fromfilter’s closure to getn: i32.

Version 2: |opt| opt.filter(|&n| n > 10)

- Here

optis&Option<i32>, but thanks to Rust’s auto-deref, calling.filter()works seamlessly. The|&n|pattern still destructures the reference inside.

Version 3: |opt| opt.filter(|n| *n > 10) * Here we keep the reference and explicitly dereference with *n when comparing.

Which one to prefer?

- We should keep the first part:

numbers.iter().map(|opt| ...) - For integers or other

Copytypes:|&n| n > 10is concise and idiomatic.

- For general types (non-Copy):

- Use

|n| *n > 10to avoid forcing a copy or clone.

- Use

V2 is better but type specific. Personally I would vote for V3 since it can be generalized.

Key Points

- Signature:

filter<P>(self, predicate: P) -> Option<T>whereP: FnOnce(&T) -> bool - Chainable: Combine with

mapfor “transform then validate” - None handling:

NonestaysNone(predicate never called) - vs if: More functional, composable with other

Option<T>methods

Find More Examples

Regular expression to use either in VSCode ou Powershell: \.filter\(\s*\|[^|]+\|[^)]*\)

🔴 - Example 13 - Working with Collections of Options - .flatten() and .filter_map()

Real-world context

Processing results where some operations fail, removing None values, transforming + filtering.

Runnable Example

Copy and paste in Rust Playground

fn parse_number(s: &str) -> Option<i32> {

s.parse().ok()

}

fn main() {

let inputs = vec!["42", "invalid", "100", "", "7"];

// Method 1: map + flatten

let numbers: Vec<i32> = inputs

.iter()

.map(|&s| parse_number(s)) // Vec<Option<i32>>

.flatten() // Remove None, unwrap Some

.collect();

println!("{:?}", numbers); // [42, 100, 7]

// Method 2: filter_map (more efficient)

let numbers2: Vec<i32> = inputs

.iter()

.filter_map(|&s| parse_number(s))

.collect();

println!("{:?}", numbers2); // [42, 100, 7]

// With transformation

let doubled: Vec<i32> = inputs

.iter()

.filter_map(|&s| parse_number(s).map(|n| n * 2))

.collect();

println!("{:?}", doubled); // [84, 200, 14]

}

Read it Aloud

”.flatten() converts Vec<Option<T>> to Vec<T> by discarding None while .filter_map(|x| optional_transform(x)) combines .map() and .flatten() in one step.”

Comments

.filter_map(|x| optional_transform(x))is more efficient for large collections

Key Points

- flatten:

Iterator<Item = Option<T>>→Iterator<Item = T> - filter_map: Combines filter + map - one pass instead of two

- Performance:

filter_mapavoids intermediate allocation - Common pattern: Processing lists where operations might fail

Find More Examples

Regular expression to use either in VSCode ou Powershell: \.flatten\(\) or \.filter_map\(

🔴 - Example 14 - Combining Multiple Options

Real-world context

Validation requiring multiple fields, coordinate systems, multi-factor authentication.

Runnable Example

Copy and paste in Rust Playground

// Method 1: Using ? operator

fn add_options(a: Option<i32>, b: Option<i32>) -> Option<i32> {

Some(a? + b?) // If either is None, return None immediately

}

// Method 2: Explicit match

fn add_options_match(a: Option<i32>, b: Option<i32>) -> Option<i32> {

match (a, b) {

(Some(x), Some(y)) => Some(x + y),

_ => None, // If either is None

}

}

// Method 3: Chaining

fn add_options_and_then(a: Option<i32>, b: Option<i32>) -> Option<i32> {

a.and_then(|x| b.map(|y| x + y))

}

fn main() {

println!("{:?}", add_options(Some(5), Some(10))); // Some(15)

println!("{:?}", add_options(Some(5), None)); // None

println!("{:?}", add_options(None, Some(10))); // None

// All three methods are equivalent

assert_eq!(add_options(Some(2), Some(3)), Some(5));

assert_eq!(add_options_match(Some(2), Some(3)), Some(5));

assert_eq!(add_options_and_then(Some(2), Some(3)), Some(5));

// Real-world: combining coordinates

fn distance(x: Option<f64>, y: Option<f64>) -> Option<f64> {

Some((x? * x? + y? * y?).sqrt())

}

println!("{:?}", distance(Some(3.0), Some(4.0))); // Some(5.0)

println!("{:?}", distance(Some(3.0), None)); // None

}

Read it Aloud

“Some(a? + b?) offers a concise early-return logic to Options<T> 2 or more option. If all Options<T> are Some(v) the processing takes place, otherwise, if any is None, early reply None.”

Comments

Key Points

- ? operator method: Cleanest for 2+ Options - reads left to right

- match method: Most explicit - good for complex conditions

- and_then method: Functional style - harder to read for multiple values

- All-or-nothing: Result is

Some(v)only if ALL inputs areSome(v)

Find More Examples

Regular expression to use either in VSCode ou Powershell: Some\(.+?\?\s*[+\-*/]\s*.+?\?\)

🔴 - Example 15 - Converting Option<&T> to Option<T> - .copied() and .cloned()

Real-world context

Working with references from collections, avoiding lifetime issues, simplifying ownership.

Runnable Example

Copy and paste in Rust Playground

fn main() {

let vec = vec![1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

// vec.first() returns Option<&i32>

let first_ref: Option<&i32> = vec.first();

println!("{:?}", first_ref); // Some(&1)

// Need Option<i32> not Option<&i32>

let first_owned: Option<i32> = vec.first().copied();

println!("{:?}", first_owned); // Some(1) - no reference

// With String (not Copy, requires cloned)

let strings = vec!["hello".to_string(), "world".to_string()];

let first_string: Option<String> = strings.first().cloned();

println!("{:?}", first_string); // Some("hello")

// Practical: avoiding lifetime errors

fn get_first_double(numbers: &Vec<i32>) -> Option<i32> {

numbers.first().copied().map(|n| n * 2)

// Without copied(): would return Option<i32> borrowing from numbers

// With copied(): returns owned i32, no lifetime issues

}

let nums = vec![10, 20, 30];

println!("{:?}", get_first_double(&nums)); // Some(20)

}

Read it Aloud

”.copied() duplicates the value inside Option<&T> to produce Option<T> (requires the Copy trait). .cloned() does the same but uses the Clone trait instead - works for non-Copy types like String.”

Comments

Key Points

- When to use: Converting

Option<&T>from collections to ownedOption<T> - copied(): For

Copytypes (i32, f64, char, etc.) - cheap bitwise copy - cloned(): For

Clonetypes (String, Vec, etc.) - potentially expensive - Lifetime escape: Lets us return

Option<T>without lifetime parameters

Find More Examples

Regular expression to use either in VSCode ou Powershell: \.copied\(\), \.cloned\(\) or \.first\(\)\.copied\(\).

Some Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Pitfall 1: unwrap() vs expect() vs unwrap_or()

let opt: Option<i32> = None;

// NOK unwrap() - panics on None with generic message

// let val = opt.unwrap(); // panics: "called `Option::unwrap()` on a `None` value"

// WARN expect() - panics with custom message (better for debugging)

// let val = opt.expect("Expected a value here!"); // panics: "Expected a value here!"

// OK unwrap_or() - provides fallback, never panics

let val = opt.unwrap_or(42);

println!("{}", val); // 42

We should never use unwrap() in production. Use expect() only when None is truly impossible (with good message). Prefer unwrap_or() or proper matching.

Pitfall 2: copied() vs cloned() Confusion

let numbers = vec![1, 2, 3];

// OK copied() for Copy types (i32)

let first: Option<i32> = numbers.first().copied();

let strings = vec!["a".to_string()];

// NOK copied() doesn't work on String (not Copy)

// let s: Option<String> = strings.first().copied(); // ERROR

// OK cloned() for Clone types

let s: Option<String> = strings.first().cloned();

We should use copied() for primitive types, cloned() for heap-allocated types (String, Vec, etc.).

Pitfall 3: Moving vs Borrowing

let opt = Some(String::from("hello"));

// NOK This moves opt

// match opt {

// Some(s) => println!("{}", s),

// None => {}

// }

// println!("{:?}", opt); // ERROR: opt was moved

// OK Borrow with as_ref()

match opt.as_ref() {

Some(s) => println!("{}", s),

None => {}

}

println!("{:?}", opt); // Works!

We should use as_ref() when we need to inspect Option<T> without consuming it.

Pitfall 4: Understanding Some(x?)

fn parse_and_wrap(s: &str) -> Option<Option<i32>> {

// NOK Confusing nested Option

Some(s.parse().ok())

}

fn parse_correctly(s: &str) -> Option<i32> {

// OK Flatten with ?

Some(s.parse().ok()?)

}

fn main() {

println!("{:?}", parse_and_wrap("42")); // Some(Some(42)) - awkward

println!("{:?}", parse_correctly("42")); // Some(42) - clean

println!("{:?}", parse_correctly("invalid")); // None

}

Some(x?) means “try to get x, if None short-circuit. Otherwise wrap in Some”. Avoids nested Options.

Quick Reference & Cheat Sheet

Extraction Methods

| Method | Returns on Some(v) | Returns on None | Panics? | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

unwrap() | T | - | ✅ Yes | 01 |

expect(msg) | T | - | ✅ Yes (with msg) | 11 |

unwrap_or(default) | T | default | ❌ No | 05 |

unwrap_or_else(f) | T | f() | ❌ No (lazy) | 05 |

unwrap_or_default() | T | T::default() | ❌ No | 05 |

Transformation Methods

| Method | Type Transform | Lazy? | Use When | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

map(f) | Option<T> → Option<U> | Yes | Transform always succeeds | 07 |

and_then(f) | Option<T> → Option<U> | Yes | Transform returns Option | 08 |

filter(p) | Option<T> → Option<T> | Yes | Conditional keeping | 12 |

flatten() | Option<Option<T>> → Option<T> | Yes | Remove nesting | 13 |

Borrowing Methods

| Method | Converts | Mutates Original? | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

as_ref() | Option<T> → Option<&T> | ❌ No | 10 |

as_mut() | Option<T> → Option<&mut T> | ✅ Yes (value inside) | 10 |

take() | Option<T> → Option<T> | ✅ Yes (sets to None) | 11 |

Checking Methods

| Method | Returns | Use When | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

is_some() | bool | Only need to know if Some(v) | 01 |

is_none() | bool | Only need to know if None | NA |

is_some_and(f) | bool | Check Some(v) + condition | NA |

Note About the Performances

- Lazy evaluation:

unwrap_or_else,map,and_then,filter- closures only run when needed - Eager evaluation:

unwrap_or- argument always evaluated - Zero-cost:

as_ref(),as_mut(),is_some(),is_none()- compile to no-ops or simple checks

Webliography

- You’re welcome to share comments or suggestions on GitHub to help improve this article.

Official Documentation

- std::option::Option - Complete API reference

- Rust Book Chapter 6.1 - Option fundamentals

- Rust by Example: Option - Practical examples

- (beginners) Would you like to check your knowledge with some flashcards? Works fine on cell phones. It is hosted for free on Heroku and may be slow to startup.

Related Articles on This Blog

- Bindings in Rust: More Than Simple Variables - Understanding ownership and borrowing.

- Rust and Functional Programming: Top 10 Functions - Iterator patterns (map, filter, etc.).

- Error Handling, Demystified - A beginner-friendly conversation on Errors.