Rust Dereferencing vs Destructuring — For the Kids 2/2

TL;DR

- Dereferencing: accessing the value behind a reference or smart pointer (e.g.,

*x, or implicit viaderef coercion). Used to read or mutate the underlying data, respecting Rust’s borrowing rules (&T,&mut T). - Destructuring: breaking apart composite values (tuples, structs, enums) using pattern matching syntax. Can move or borrow parts depending on context.

The Post is in 2 Parts

- The introduction is the same in both posts

- Rust Dereferencing vs Destructuring — For the Kids 1/2

- Rust Dereferencing vs Destructuring — For the Kids 2/2

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Patterns and Destructuring Patterns in Rust

- Destructuring: A Smooth Start

- Destructuring: Partial and Range Destructuring

- Destructuring:

structofi32withlet - Destructuring:

structofStringwithlet - Destructuring:

structof&strwithlet - Destructuring:

structof&strwithlet - Destructuring:

enumwithlet - Destructuring:

enumwithlet - Destructuring: Function & Closure Parameters

- Destructuring: in

forLoops with.enumerate() - Destructuring:

forLoop over Array Slices - Destructuring: Destructuring Pattern in

forLoop - Destructuring: Filter and Destructuring Pattern in

forLoop - Rust Gotchas: Destructuring Edition

- Answers to Questions from the Introduction

- Dereferencing vs Destructuring in Rust — Key Takeaways

- Conclusion

Introduction

If you’re learning Rust and the concepts of ownership, borrowing, and references still feel unfamiliar or intimidating — you’re not alone.

Coming from languages like Python or C++, it’s easy to assume that Rust’s &, *, and smart pointers behave the same way. But Rust has its own philosophy, built around memory safety and enforced by strict compile-time rules.

This article aims to clarify the difference between dereferencing and destructuring — two concepts that are often confused, especially outside of match expressions.

Why the Confusion?

At first glance, dereferencing (using *) and destructuring (in let, if let, or match patterns) can look similar when working with references. Consider the following lines:

let r = &Some(5);

if let Some(val) = r {

println!("val = {val}");

}

No explicit *r — yet the pattern matches. How?

Now look at this one-liner:

let Some(x) = &Some(42);

Is this dereferencing, destructuring, or both?

And then:

let b = Box::new((42, "hello"));

let (x, y) = *b;

let (x, y) = b; // Doesn't compile

The three examples seem simple — but do you really understand why they behave this way?1

If you already know the answers, maybe this article isn’t for you. But if you’ve ever hesitated, been surprised by a compilation error, or struggled to explain why one line works and another doesn’t… then you’re in the right place.

This article won’t just define dereferencing and destructuring — it will show you how Rust treats them, how the compiler helps (or confuses) you, and when the distinction truly matters.

What This Post in 2 Parts Covers

- Dereferencing: Part 1/2. How to access values through references and smart pointers (Box, Rc, RefCell), and how mutability affects this.

- Destructuring: Part 2/2. How to unpack values in let, match, and function or closure parameters — including when working with references.

No multithreading knowledge required. For a threaded use case, see this post on Multithreaded Mandelbrot sets (in French).

Whether you’re just starting with Rust or adjusting your mental model, this post is for you.

Now that we’ve seen in Part 1 how to follow pointers, it’s time to open the box and peek inside with destructuring!

Patterns and Destructuring Patterns in Rust

What is Destructuring? Destructuring is the act of using a pattern to break a value apart and extract its inner pieces. As we will see, we are not just assigning a value, we are unpacking it. However before diving into destructuring, it’s important to understand what a pattern is.

In Rust, a pattern is a syntax that matches the shape of a value. You’ve probably already seen patterns in match statements, if let, or while let — but patterns are everywhere: in let bindings, function and closure parameters, and for loops.

OK… But what is a pattern?

A pattern tells the compiler: “I expect a value of a certain shape — and I want to extract pieces from it.” Ok, let’s not waste time and go and see some code.

Destructuring: A Smooth Start

Too often we, me first, associate the concept of destructuring to match but this is too restrictive. Let’s start with some let statements. Copy and paste the code below in the Rust Playground then hit CTRL + ENTER

fn destructuring01() {

println!("\nDestructuring 01 : 101\n");

let (x, y) = (1, 2); // (x, y) is a pattern

println!("{x}, {y}");

let (x, y) = (1, 3.14); // tuple => we can have different data type

println!("{x}, {y}");

let [a, b, c] = [10, 20, 30]; // [a, b, c] is a pattern

println!("{a}, {b}, {c}");

let x = 42; // `x` is a very simple pattern: it matches any value and binds it to the name `x`

println!("{x}");

let ((x1, y1), (x2, y2)) = ((1, 2), (3, 4)); // nested destructuring

println!("{x1}, {y1}, {x2}, {y2}");

}

fn main(){

destructuring01();

}

Expected output

Destructuring 01 : 101

1, 2

10, 20, 30

42

1, 2, 3, 4

Explanations

- As I said, destructuring is the act of using a pattern to break a value apart and extract its inner pieces. In this context, a pattern is a syntax that matches the shape of a value. I like to compare it to regular expressions. Does the sequence of digits look like a phone number? If yes, extract the relevant parts.

- The first

letstatement matches(x, y)to(1, 2). Once the shapes match, the value 1 is assigned toxand 2 toy. I told you. A smooth start.- I hope you know why

letis a statement and not an expression. If you’re not sure, you can start with this Computer Science Vocabulary page then this page.

- I hope you know why

- Let’s talk again about the first

letbut with other words. Just to make sure… When destructuring, the pattern, the left-hand side must match the shape of the value on the right hand side. In this case, a 2-element tuple is matched by a 2-element pattern.- We are not surprised with a line like

let x = 1;. We understand that the Rust compiler infer the data type ofx. This also happens here. After all, with or without destructuring, the statement is aletstatement.

- We are not surprised with a line like

- The second

letstatement is similar to the first one except thatxandyhave different data type. Nothing magic here. Tuples can hold values of different datatype. The more important question is: “Does the shape on the left-hand side match the shape on the right-hand side?” This must be checked first, because even if both sides are tuples, they might have different numbers of elements. Once the shape is validated, one could imagine that theletstatement is unfold as a set of 2 “regular”letstatements (let x=1;andlet y=2;) - The third

letis similar to the first one but since we are matching two arrays,a,bandcwill all have the same data type (the type of the element in the rhs array). Again one coud imagine that once the shape is checked, the let statement is unfold as a set of 3 lines similar to :let a:i32 = 10;. You get the idea. - The fourth might be surprising, but first, if the notion of binding is not crystal clear, you can read this post (US). Here, the pattern on the left (

x) is a simple binding — it matches any value and assigns it tox. - The last

letstatement shows nested destructuring, where like with Russian Dolls, match act at different levels. Again think at the regular expression where we can define sub-patterns (also called groups).

At this point I would like to decompose the “process” in 2 steps. Indeed, everything looks like :

- Matching : Check if the left-hand side has the same shape as the right-hand side (think regular expressions).

- Destructuring : If matching is successful, break down the value and assign the components accordingly — effectively unfolding the

letinto multiple individualletstatements.

So, the good news is: everything we already know about let statements applies here too. For instance, destructuring works with custom data types, references, dereferencing, and so on. This also means that some bindings will move, while others copy, and in some cases, the compiler may perform deref coercion behind the scene. That’s part of the fun…

Let’s keep all this in mind for the moment and let’s look at some of syntactic options that the destructuring brings with it.

Destructuring: Partial and Range Destructuring

As explained, destructuring can be seen as a 2 steps process : matching then unfolding. As a developer we can imagine that during the matching part, it is useful to enhance the syntax of the left-hand side so that it can describe the set of items with some wildcards. Think about what we can do when we want to list the files of the current directory : ls my_file.*, or ls my_?ile.* for example.

Run the code below :

fn destructuring02() {

println!("\nDestructuring 02 : partial and range destructuring\n");

let (mut x, ..) = (41, 2, 3); // ignore the rest

x += 1;

println!("x: {x}");

let (.., z) = (1, 2, 101); // ignore the rest

println!("z: {z}");

let age = 15;

match age {

1..=17 => println!("No way to access the dance floor."),

_ => println!("Welcome to Studio 54!"),

}

let x = Some(1984);

match x {

Some(y) if y > 1964 => println!("Your are young."),

Some(_) => println!("Your are old."),

None => println!("Nothing."),

}

let pair = ("Hari Seldon", 12050);

let (_, just_the_year) = pair;

println!("We only care about the year: {}", just_the_year);

let num = Some(10);

match num {

Some(n @ 1..=10) => println!("In the range [1;10]: {n}"),

_ => println!("Other"),

}

}

Expected output

Destructuring 02 : partial and range destructuring

x: 42

z: 101

No way to access the dance floor.

Your are young.

We only care about the year: 12050

In the range [1;10]: 10

Explanations

This post is not a reference so I just show few of the “facilities” available in the matching step. The reference is here.

let (mut x, ..) = (41, 2, 3);: shows that we can use amutand that it is possible to extract only the first elementlet (.., z) = (1, 2, 101);: shows we can extract only the last element- This is not shown but yes you can write

let (x, .., z) = (31, 32, 33, 34, 35);

- This is not shown but yes you can write

- The third example (

1..=17 => println!(...) : shows how the pattern can be tested against a range of values - The fourth example (

Some(y) if y > 1964 => println!(...) : shows how to add a pattern guard in amatch let (_, just_the_year) = pair;: shows how to extract the parts of interest- The last example (

Some(n @ 1..=10) => println!(...) : shows binding with subpattern (aka @ binding pattern). It brings filtering and binding at the same time.

To keep in mind

Destructuring is a 2 steps process (matching, unfolding) and in the matching step we have means to describe the components we want to extract (think at

ls *.rs)

Let’s stay on the subject of partial destructuring and study the code below, in which we want to extract a member from a tuple that is not of primitive data type (String for example)

fn destructuring02_bis() {

println!("\nDestructuring 02 bis : partial and range destructuring\n");

let data = (String::from("Obi-Wan"), 42);

// This would move the String out of the tuple, making it unusable afterward:

let (s, _) = data;

println!("s: {}", s);

// println!("data.0: {}", data.0); // does not compile

let mut data = (String::from("Obi-Wan"), 42); // re-create data

// Instead, we can use `ref` to borrow the String by reference

let (ref s_ref, _) = data;

println!("Using `ref`: {}", s_ref); // s_ref is a &String

println!("Original still usable: {}", data.0); // data.0 is still valid

// Now let's use `ref mut` to get a mutable reference to the String

let (ref mut s_mut_ref, _) = data;

s_mut_ref.push_str(" Kenobi");

println!("Using `ref mut`: {}", s_mut_ref); // Modified through &mut String

println!("Original mutated: {}", data.0); // Shows the mutation

}

Expected output

Destructuring 02 bis : partial and range destructuring

s: Obi-Wan

Using `ref`: Obi-Wan

Original still usable: Obi-Wan

Using `ref mut`: Obi-Wan Kenobi

Original mutated: Obi-Wan Kenobi

Explanations

datais a tuple consisting of aString(not primitive) and ani32(primitive)- We extract (

let (s, _) = data;) and print the string part of the data. - The issue is that since String cannot Copy it is moved and

datais no longer available - The commented-out

println!line does not compile

What can we do ?

- We must re-create

dataas a mutable tuple (let mut data = (String::from("Obi-Wan"), 42);) - Then we use

refin the pattern to create an immutable reference instead of moving the value

If we need to be able to modify the extracted sub component

- We use

ref mutwhich allows mutating the original value via a mutable reference.

Just to make sure we talked about it… ref (ref_mut) can be used in match expressions as well. See below :

fn destructuring02_ter() {

println!("\nDestructuring 02 ter : ref in match expression\n");

let val = Some(String::from("Kenobi"));

// Match using `ref` to borrow the inner String instead of moving it

match val {

Some(ref x) => {

// x is a &String (reference), so we can use it without consuming `val`

println!("Borrowed from Some: {}", x);

},

None => println!("Got nothing"),

}

// We can still use `val` here because we didn't move its content

match val {

Some(x) => println!("Moved from Some: {}", x),

None => println!("Still nothing"),

}

// println!("{:?}", val); // does not compile: `val` was moved

}

Expected output

Destructuring 02 ter : ref in match expression

Borrowed from Some: Kenobi

Moved from Some: Kenobi

Explanations

valis anOptionon a non primitive data type (aStringhere)- In the first

matchexpression- We write

Some(ref x)(rather thanSome(x)) because, as in the previous code snippet, we don’t want to move (and loose)val xis of type&Stringso we shouldprintln!*xbut thanks to deref coercion we can usex

- We write

- In the second

match expression- We can use

valbecause it was not moved - However, here, we consume

val(match val {...)

- We can use

- After this second match,

valis no longer accessible - The commented-out

println!does not compile

Hm… What is the difference between ref x and *x? Again let’s use some code :

fn main() {

let &x = &42; // &x is a pattern

println!("x = {}", x); // x = 42

let x = &42; // a reference

println!("x = {}", x); // x = 42

println!("*x = {}", *x); // x = 42

let ref x = 42; // a reference

println!("x = {}", x); // x = 42

println!("*x = {}", *x); // x = 42

}

let &x = &42;- Right:

&42is a reference to an integer (&i32) - Left:

&xis a pattern that says: “I expect a reference, and I want to extract its value” - The

&in the pattern means: “I want to deconstruct a reference”. - Rust compiler implicitly dereferences

&42(*(&42)) to extract 42, and assigns it tox.

- Right:

let x = &42;- Right :

&42is a reference to an integer (&i32) - Left :

xis a binding whose value is a reference to the value

- Right :

let ref x = 42;- Right: 42 is an

i32. - Left:

ref xmeans: “Instead of getting the value, I want a reference to the value”

- Right: 42 is an

The second and third lines are functionally equivalent but the context differs

&is an operator, used in expression, on the right hand side (rhs)refis keyword, used in patterns (let,match,if let…) to create a reference.- We cannot use

&in a pattern because it already have another meaning (“I expect a reference, and I want to extract its value”)

- We cannot use

Destructuring: struct of i32 with let

fn destructuring03() {

println!("\nDestructuring 03 : struct of i32 with let");

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Point4D {

x: i32,

y: i32,

z: i32,

t: i32,

}

let pt = Point4D { x: 1, y: 2, z: 3, t: 2054 };

let Point4D { x, t, .. } = pt; // copy

println!("x: {x} and time: {t}");

println!("{:?}", pt); // pt is available

}

Expected output

Destructuring 03 : struct of i32 with let

x: 1 and time: 2054

Point4D { x: 1, y: 2, z: 3, t: 2054 }

Explanations

This one is easy.

- We create a new type named

Point4D. This is astructwith 4 fields of typei32(struct Point4D {...).#[derive(Debug)]is mandatory if we want toprintln!("{:?}..." - Then we create and initialize a variable

ptof that type (let pt = Point4D { x: 1, y: 2, z: 3, t: 2054 };) - The line

let Point4D { x, t, .. } = pt;is aletstatement that uses pattern destructuring to extract the fieldsxandtfrom thePoint4Dstruct, while ignoring the other fields. - The pattern “wants” a variable of type

Point4Dthat it will break apart (let Point4D { x, t, .. } = pt;)- Note that no matter the order, we only extract

xandt - Since the components are primitive type (

i32),ptis copied before the components are extracted

- Note that no matter the order, we only extract

- At the end, the 2

println!show how to use the extracted components and demonstrate thatptremains available after theletstatement.

Destructuring: struct of String with let

fn destructuring03_bis() {

println!("\nDestructuring 03 bis : struct of String with let");

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Person {

last_name: String,

first_name: String,

}

let luke = Person {

last_name: "Skywalker".to_string(),

first_name: "Luke".to_string()

};

let Person {last_name, first_name } = luke; // move because String does'nt have Copy trait

println!("{}-{}", last_name, first_name);

// println!("{:?}", luke); // does not compile

}

Expected output

Destructuring 03 bis : struct of String with let

Skywalker-Luke

Explanations

This is the same code except that the struct is now a struct of non-primitive datatype (part of the String in on the stack but the “chars” (the buffer) are on the heap). They are not primitive datatype like i32 or &str…

- We create a new type named

Person. This is astructwith 2 fields of typeString. - Then we create and initialize a variable

lukeof that type (let luke = Person { ...) - The

letstatement (let Person {last_name, first_name } = luke;) uses pattern destructuring to extract the fields - The patterns “wants” a variable of type

Personthat it will break apart (let Person {last_name, first_name } = luke;)- Since the components are String

lukeis moved before the components are extracted

- Since the components are String

- The

println!show how to use the extracted components - The commented-out

println!does not compile becauselukehas been moved and is no longer available (RIP)

Destructuring: struct of &str with let

In order to avoid the move (and the lost of luke) we may decide to use string slice (&str). The first idea of code we may have does not compile

fn destructuring03_ter() {

println!("\nDestructuring 03 ter : struct of `&str` with let");

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Person<'t> {

last_name: &str,

first_name: &str,

}

let luke = Person {

last_name: "Skywalker",

first_name: "Luke"

};

let Person {last_name, first_name } = luke;

println!("{}-{}", last_name, first_name);

println!("{:?}", luke);

}

The compiler complains because it wants to get, from us, the confirmation that the string slices will live long enough (it says : “expected named lifetime parameter” on each of the struct Person fields)

Below is a version that compile :

fn destructuring03_ter() {

println!("\nDestructuring 03 ter : struct of `&str` with let");

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Person<'t> {

last_name: &'t str,

first_name: &'t str,

}

let luke = Person {

last_name: "Skywalker",

first_name: "Luke"

};

let Person {last_name, first_name } = luke; // copy of &str

println!("{}-{}", last_name, first_name);

println!("{:p} - {:p}", last_name, first_name);

println!("{:?}", luke); // does compile

println!("{:p} - {:p}", luke.last_name, luke.first_name);

}

Expected output

Destructuring 03 ter : struct of &str with let

Skywalker-Luke

Pointer { addr: 0x5bb07cc760d7, metadata: 9 } - Pointer { addr: 0x5bb07cc76057, metadata: 4 }

Person { last_name: "Skywalker", first_name: "Luke" }

Pointer { addr: 0x5bb07cc760d7, metadata: 9 } - Pointer { addr: 0x5bb07cc76057, metadata: 4 }

Explanations

Basically, it’s the same code as the one that used String. We use &str instead and we had to indicate the lifetime

- We create a new type named

Person. This is astructwith 2 fields of type&'t str(&str+ lifetime annotation) - Then we create and initialize a variable

lukeof that type (let luke = Person { ...) - The

letstatement (let Person {last_name, first_name } = luke;) uses pattern destructuring to extract the fields - In the

letstatement, the patterns “wants” a variable of typePersonthat it will break apart (let Person {last_name, first_name } = luke;)- Since the components are of type

&str,lukeis copied before the components are extracted

- Since the components are of type

- The first 2

println!show how to use extracted components and display their respective addresses - The last 2

println!demonstrate thatlukeis still available after theletstatement. They also display the addresses of the components so that we can check they are the same as the one already printed. - This confirm that when the copy took place only the addresses were copied, not the buffer (the “chars”).

Destructuring: struct of &str with let

Here is another implementation of the same code. It does exactly the same thing and is not faster/slower. Only the let statement syntax differs.

fn destructuring03_qua() {

println!("\nDestructuring 03 qua : struct of &str with let");

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Person<'t> {

last_name: &'t str,

first_name: &'t str,

}

let luke = Person {

last_name: "Skywalker",

first_name: "Luke"

};

let &Person {last_name, first_name} = &luke;

// The line above is similar to the 2 lines below

// let ref = &luke;

// let Person {last_name, first_name} = ref;

println!("{} - {}", last_name, first_name);

println!("{:p} - {:p}", last_name, first_name);

println!("{:?}", luke);

println!("{:p} - {:p}", luke.last_name, luke.first_name);

}

Expected output

Destructuring 03 qua : struct of &str with let

Skywalker - Luke

Pointer { addr: 0x56815ba0b0d7, metadata: 9 } - Pointer { addr: 0x56815ba0b057, metadata: 4 }

Person { last_name: "Skywalker", first_name: "Luke" }

Pointer { addr: 0x56815ba0b0d7, metadata: 9 } - Pointer { addr: 0x56815ba0b057, metadata: 4 }

Explanations

Code similar to the previous one except the let statement.

- The

letstatement (let &Person {last_name, first_name} = &luke;) uses pattern destructuring to extract the fields - In the

letstatement, the pattern “wants” a reference to a Person that it will dereference before to extract the parts - It does a

*(&luke)to get access toluke. Then the components are extracted - The 4

println!display exactly the same information and confirmationlukewas copied- Only the addresses were copied, NOT the buffer.

Destructuring: enum with let

fn destructuring04() {

println!("\nDestructuring 04 : enum with let\n");

enum Role {

Emperor,

Trader(String),

Scientist { name: String, field: String },

}

let characters = vec![

Role::Emperor,

Role::Trader("Hober Mallow".to_string()),

Role::Scientist {

name: "Hari Seldon".to_string(),

field: "Psychohistory".to_string(),

},

];

for role in characters { // role is Role, characters is consumed

match role {

Role::Emperor => println!("The Emperor rules... vaguely."),

Role::Trader(name) => println!("A trader named {name}"),

Role::Scientist { name, field } => {

println!("Scientist {name} specializes in {field}")

}

}

}

println!("{}, characters"); // does not compile

let Some(x) = Some(5) else { todo!() }; // Some is an enum

println!("x: {x}");

}

Expected output

Destructuring 04 : enum with let

The Emperor rules... vaguely.

A trader named Hober Mallow

Scientist Hari Seldon specializes in Psychohistory

x: 5

Explanations

The first part of the sample code shows how one could build and print a collection of characters using a for loop and a match expression.

- First we define

Roleas anenum(enum Role {...) which have three variants:- Emperor, a

unitvariant with no associated data, - Trader, a

tuplevariant containing a singleString, - Scientist, a

structvariant with two named fields: name (String) and field (String).

- Emperor, a

- Then we build a collection of characters in a vector (

let characters = vec![...)- The collection have 3 members

- Each element is defined and initialized

- Now comes the interesting part where we print the content of the collection using a

forloop and amatch- At each iteration the current role is matched with all the possible variants

- Depending the role, more or less information are printed

Important : We must realize that in the for loop, role is of type Role. Indeed, we pass characters to the for loop, so behind the scene, the for loop calls .into_iter() which consume the vector and return a Role.

At the very end, since Some is an enum, the one on the rhs is destructured and its inner value is use to initialize x.

Destructuring: enum with let

Since we may not want to consume the collection of characters, the easiest way of doing is to use a reference and to destructure it in the match expression.

fn destructuring04_bis() {

println!("\nDestructuring 04_bis : enum with let\n");

#[derive(Debug)]

enum Role {

Emperor,

Trader(String),

Scientist { name: String, field: String },

}

let characters = vec![

Role::Emperor,

Role::Trader("Hober Mallow".to_string()),

Role::Scientist {

name: "Hari Seldon".to_string(),

field: "Psychohistory".to_string(),

},

];

for role in &characters { // role is &Role, characters not consumed

match role {

Role::Emperor => println!("The Emperor rules... vaguely."),

Role::Trader(name) => println!("A trader named {name}"),

Role::Scientist { name, field } => {

println!("Scientist {name} specializes in {field}")

}

}

}

println!("{:?}", characters);

let Some(x) = Some(5) else { todo!() }; // Some is an enum

println!("x: {x}");

}

Expected output

Destructuring 04_bis : enum with let

The Emperor rules... vaguely.

A trader named Hober Mallow

Scientist Hari Seldon specializes in Psychohistory

[Emperor, Trader("Hober Mallow"), Scientist { name: "Hari Seldon", field: "Psychohistory" }]

x: 5

Explanations

- The key difference is the way we pass

charactersto theforloop. - By reference (

for role in &characters {...) - In the

matchexpression, this timeroleis of type&Role

Hep, hep, hep! Break! OK, but the rest of the code is the same. How can this work ? You are right. Strictly speaking we should write something like :

match role {

&Role::Emperor => ...

&Role::Trader(ref name) => ...

&Role::Scientist { ref name, ref field } => ...

}

Indeed, in the for loop role is of type &Role so the match can be done with values of type &Role.

However, behind the scene, Rust compiler will do an implicit dereferencing of the pattern (see this page).

In plain English :

- The compiler detects

&Roleon thematchside andRoleon the variant side - The compiler automatically does a

*(role). In terms of data type it is similar to do a*(&Role). Tadaa! Now, on the match side, the compiler have aRolein hands it can match withRolevalues on the variant side.

To keep in mind

In a

matchexpression, Rust automatically applies a series of*(references)as long as this allows the pattern on thematchside to match the values type on the variants side.

To keep in mind

Pass reference to

forloop (for val in &array {...)

Destructuring: Function & Closure Parameters

fn destructuring05() {

println!("\nDestructuring 05 : function & closure parameters\n");

fn print_coordinates((x, y): (i32, i32)) {

println!("Function received: x = {}, y = {}", x, y);

}

let point = (10, 20);

print_coordinates(point);

println!("{:?}", point);

fn print_full_name((first, last): (String, String)) {

println!("Function received: First = {}, Last = {}", first, last);

}

let chief = ("Martin".to_string(), "Brody".to_string());

print_full_name(chief);

// println!("{:?}", chief);// does not compile

let points = vec![(1, 2), (3, 4), (5, 6)];

points.iter().for_each(|&(x, y)| {

println!("Point: x = {}, y = {}", x, y);

});

println!("Point: {:?}", points);

}

Expected output

Destructuring 05 : function & closure parameters

Function received: x = 10, y = 20

(10, 20)

Function received: First = Martin, Last = Brody

Point: x = 1, y = 2

Point: x = 3, y = 4

Point: x = 5, y = 6

Point: [(1, 2), (3, 4), (5, 6)]

Explanations

- We define the function

print_coordinatesinside a function (destructuring05) - A

pointvariable is defined and initialized (let point = (10, 20);) - Then it is used as an argument when we call

print_coordinates(print_coordinates(point);) - The destructuring happens when the parameters are defined (

fn print_coordinates((x, y): (i32, i32)) {...) - Since the data types of

pointare primitive (implement Copy trait),pointis passed by value (it is copied) pointis still available after the call toprint_coordinatesand it can be printed

As we can expect, this is another story when the components are not primitive. To illustrate the point we:

- Define a function

print_full_name chiefis a tuple with 2 String. String do no implement Copy- We call

print_full_namewithchiefas an argument - Since

chiefis based on non primitive data type, it is moved - The function parameter pattern

(first, last): (String, String)performs destructuring directly in the function’s argument list. - It moves the two

Stringvalues from the incoming tuple into the local variablesfirstandlast. These are new bindings with new stack addresses, although they may still point to the same heap-allocated buffers as the original values. - The commented-out

println!does not compile sincechiefis gone (and the sharks are not guilty)

Destructuring: in for Loops with .enumerate()

Do you remember, not September (EWF, 1978), but destructuring04() and destructuring04_bis() where we passed the array by value then by reference. Here, we want to avoid the raw for loop (“no raw loops”, said Sean Parent in 2013). To do so we can use an iterator to visit an iterable (think of a vector, for example) from start to end.

fn destructuring06() {

println!("\nDestructuring 06 : in for loops with .enumerate()\n");

let characters = vec!["Hari", "Salvor", "Hober"];

for (index, name) in characters.iter().enumerate() {

println!("Character #{index} is {name}");

}

let characters = vec!["Harry".to_string(), "Hermione".to_string(), "Ron".to_string()];

for (index, name) in characters.iter().enumerate() {

println!("Character #{index} is {name}");

}

}

Expected output

Character #0 is Hari

Character #1 is Salvor

Character #2 is Hober

Character #0 is Harry

Character #1 is Hermione

Character #2 is Ron

Explanations

The key point here is that in a for loop, the variable immediately after the for keyword is a pattern. That’s why we can destructure tuples directly inside the loop. Once we have this in mind, understanding the code is easier.

To keep in mind

The variable immediately after the

forkeyword is a pattern.

- We create a vector of

characters(&str) withlet characters = vec!["Hari", "Salvor", "Hober"]; - We iterate and enumerate over the vector (

for (index, name) in characters.iter().enumerate(){...)- At each iteration

.iter()returns a reference to a&str(&&str).enumerate()wraps it into a tuple(usize, &&str)

- Destructuring

index: binds tousizename: binds to&&str

- Printing

- The compiler will apply implicit deref coercion

- It will do something like

*(&&str)=&str=> A type which can be printed as usual.

- At each iteration

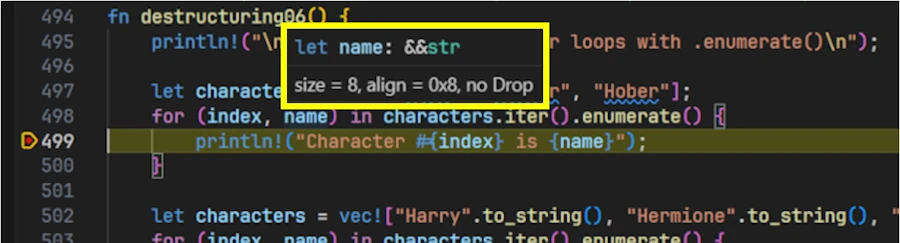

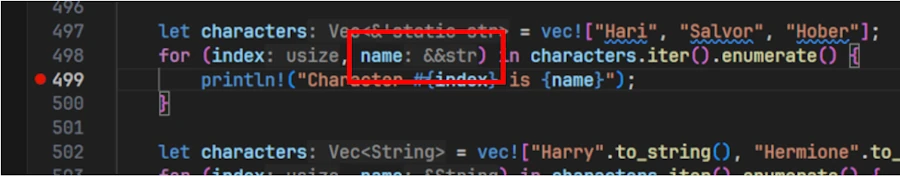

Hum, hum… How can you be so sure about what you say ? “Trust in me, just in me…”. No, don’t trust people, check by yourself and here the debugger is your best friend. Below I put a breakpoint on the first println! and hover name. Do you see the data type in the yellow rectangle?

Under VSCode, with my setup, if I hit CTRL + ALT I can see the data type as overlays. Can you see the content of the red rectangle?

This said, and always about the first for loop, if you have time play with the code below (Rust Playground is your second best friend after the debugger) :

fn destructuring06_bis() {

println!("\nDestructuring 06 bis: in for loops with .enumerate()\n");

let characters = vec!["Hari", "Salvor", "Hober"];

for (index, name) in characters.iter().enumerate() {

println!("Character #{index} is {name}");

let bob = *name; // &str

println!("{}", bob);

// let bob = **name; // str, does not compile, no size known at compile-time

// println!("{}", bob);

// let bob = ***name; // ???, does not compile

// println!("{}", bob);

let bob = &name; // &&&str

println!("{}", bob);

}

}

It is time now to talk about the second for loop

let characters = vec!["Harry".to_string(), "Hermione".to_string(), "Ron".to_string()];

for (index, name) in characters.iter().enumerate() {

println!("Character #{index} is {name}");

}

- We create a vector

charactersofStringwithlet characters = vec!["Harry".to_string()... - We iterate and enumerate over the vector (

for (index, name) in characters.iter().enumerate(){...)- At each iteration

.iter()returns a reference to aString(&String).enumerate()wraps it into a tuple(usize, &String)

- Destructuring

index: binds tousizename: binds to&String

- Printing

- The compiler will apply implicit deref coercion

- It will do something like

*(&String)=String=> A type which can be printed as usual.

- At each iteration

In other words, we should have written the first line of the loop (*name), but, thanks to deref coercion we can write the second.

for (index, name) in characters.iter().enumerate() {

println!("Character #{index} is {}", *name);

println!("Character #{index} is {name}");

}

Destructuring: for Loop over Array Slices

fn destructuring07() {

println!("\nDestructuring 07 : for loop over array slices\n");

let coordinates = vec![[1, 2], [3, 4], [5, 6]];

for &[x, y] in &coordinates {

println!("x: {}, y: {}", x, y);

}

// Alternative: without destructuring

for coord in &coordinates {

println!("coord[0]: {}, coord[1]: {}", coord[0], coord[1]);

}

}

Expected output

Destructuring 07 : for loop over array slices

x: 1, y: 2

x: 3, y: 4

x: 5, y: 6

coord[0]: 1, coord[1]: 2

coord[0]: 3, coord[1]: 4

coord[0]: 5, coord[1]: 6

Explanations

for &[x, y] in &coordinates may look like we’re referencing, but &[x, y] is a pattern. Indeed, it is placed after the for keyword. This said, let’s read the code :

- we create a vector of 2-element arrays of

i32(let coordinates = vec![[1, 2]...) coordinatesis passed by reference to theforloop.- We are borrowing

coordinatesnot consuming it - At each iteration, the

forloop handles references to[i32, 2](&[i32; 2]) &[x, y]is a destructuring pattern that matches a reference to a 2-element array- The compiler matches

&[x, y]with each&[i32; 2] - Since

i32is primitive, it has the Copy trait, the values are copied intoxandy(no ownership issues). - The second for loop shows how we can survive without destructuring

Destructuring: Destructuring Pattern in for Loop

This is the part that broke my brain when I first encountered it and what motivated me to write this post.

When iterating over a vector of strings by reference (&Vec<String>), I naively thought that writing for &s in &foundation{...} meant “give me the reference and then give me the value.” But that’s not what’s happening.

fn destructuring08() {

println!("\nDereferencing 08 : destructuring pattern in for loop\n");

let foundation: Vec<String> = vec!["Hari Seldon", "Salvor Hardin", "Hober Mallow", "The Mule"]

.into_iter()

.map(|s| s.to_string())

.collect();

// for &s in &foundation { // does not compile

for s in &foundation {

println!("String is : {}", s);

}

}

Expected output

Dereferencing 08 : destructuring pattern in for loop

String is : Hari Seldon

String is : Salvor Hardin

String is : Hober Mallow

String is : The Mule

Explanations

- Again, in Rust, the expression after

forkeyword is always a pattern — and here,&sis a destructuring pattern, not a reference. - We create a vector of

Stringnamedfoundation foundationis passed by reference to theforloop- We are borrowing

foundationnot consuming it - Each element iterated is a

&String, not aString - The commented-out

forloop (for &s in &foundation {...) does not compile and here is why :- It tries to match a

&Stringwith the destructuring pattern&s - This would only work if

swould be of typeString - String type does not implement the Copy trait and and implicit cloning is not allowed

- So it does not complie

- It tries to match a

- The working

for(for s in &foundation {)- It matches

&Stringwith the destructuring patterns - This can work because a reference (an address) is a primitve type which can be copied

sis of type&String- Without deref coercion we should have to write

println!("String is : {}", *s);(or.as_str()) - Rust allow us to write

println!("String is : {}", s);

- It matches

To keep in mind

In a for loop, if we write

&s, we are telling the compiler: “I want to destructure a reference and bind the value inside it.” It’s not the same as taking a reference.

To keep in mind

This may not be the canonical way of doing but… Here is how I design the destructuring pattern. I read the for loop backward

- What is the type of the iterated element (ex:

String)- Is it primitive or not (Copy or not, ex: No)

- Do I get a reference to it or not (ex: Yes)

- Design (ex:

s,sis&String)

Destructuring: Filter and Destructuring Pattern in for Loop

Patterns can be used in loops to filter and destructure in a single step, let’s see how.

fn destructuring09() {

println!("\nDestructuring 09 : filter and destructuring pattern in a for loop\n");

let maybe_scores = vec![Some(10), None, Some(30)];

// The pattern is a reference to an Option, so we match &Some(x)

for &opt in &maybe_scores {

match opt {

Some(score) => println!("Score: {}", score),

None => println!("No score"),

}

}

// Alternative: filter out None before the loop

for score in maybe_scores.iter().filter_map(|opt| opt.as_ref()) {

println!("Got a score (filter_map): {}", score);

}

// Alternative : if-let inside the loop body

for maybe in &maybe_scores {

if let Some(score) = maybe {

println!("Score via if-let: {}", score);

}

}

// Alternative : flattening the Some directly in the iterator

for score in maybe_scores.iter().flatten() {

println!("Score via flatten: {}", score);

}

}

Expected output

Destructuring 09 : filter and destructuring pattern in a for loop

Score: 10

No score

Score: 30

Got a score (filter_map): 10

Got a score (filter_map): 30

Score via if-let: 10

Score via if-let: 30

Score via flatten: 10

Score via flatten: 30

Explanations

- We create

may_scoresa vector ofOption<i32> may_scoresis passed by reference to theforloop- We are borrowing

may_scoresnot consuming it - Each element iterated is a

&Option<i32>, not aOption<i32>

First loop (for &opt in &maybe_scores {...)

- It matches

&Option<i32>with the destructuring pattern&opt optis anOption<i32>- It is used in the body of the

forloop in amatchexpression - All variants of the options are listed

Second for loop (for score in maybe_scores.iter().filter_map(|opt| opt.as_ref()) {...)

- This one is smart

maybe_scores.iter()creates an iterator onmaybe_scoreselements.filter_map(|opt| opt.as_ref())applies a filtering and transformation operationoptis the output ot the previous iteratorfilter_maptakes a closure which must returnOption<T>- For each element :

opt.as_ref()converts&Option<i32>toOption<&i32>- So here, if the element is

Some(value),as_ref()returnsSome(&value)otherwise it returns None filter_mapkeeps only values where closure returnsSome, and extracts the internal value

- For each element :

- The result of

filter_mapis an iterator on references to non-None values

- Then the score are printed

Third loop (for maybe in &maybe_scores {...)

- Use an

if letin the loop body maybeis&Option<i32>- With

if let Some(score) = maybescore get the value ofmaybeif the latare is not None - The score is printed

Fourth loop (for score in maybe_scores.iter().flatten() {...)

.flatten()is use to remove 1 level of nesting on an iterator of iterators.- When called on an iterator of Option values,

.flatten()automatically filters out all None variants and unwraps the Some variants. - Here this means we iterate over the actual score values that exist, completely skipping any None entries

Any tips and tricks to share ? Here are a few common traps and surprises you might encounter (I did)

Rust Gotchas: Destructuring Edition

1. Shadowing Without Realizing It

You might accidentally shadow variables, leading to confusion or bugs if the shadowed value was still needed later.

let x = 5;

let (x, y) = (10, 20); // This shadows the previous `x`

2. Destructuring by Move (Not Copy)

Destructuring consumes values unless they implement Copy. Be careful with types like String, Vec, or custom structs.

let s = String::from("hello");

let (s1,) = (s,); // s is moved, not copied

// println!("{}", s); // error: borrow of moved value

3. Patterns Are Not Always Exhaustive in Match Arms

Failing to match all variants can cause a compilation error — or worse, if using _ too liberally, you might silently ignore important cases.

enum MyEnum { A(i32), B(String), C }

let x = MyEnum::C;

match x {

MyEnum::A(n) => println!("A({n})"),

MyEnum::B(_) => println!("B"),

// MyEnum::C not covered!

}

4. Borrowing in if let and while let Is Tricky

To keep ownership, use a reference:

let opt = Some(String::from("hello"));

if let Some(s) = opt {

println!("{}", s);

}

// println!("{:?}", opt); // moved!

if let Some(ref s) = opt { ... }

5. Destructuring &T vs T

If you destructure a reference (&pair), your pattern must also use &. This often confuses newcomers.

let pair = (1, 2);

let &(a, b) = &pair; // Need `&` pattern to destructure a reference

6. Too Much Pattern Nesting Hurts Readability

Consider breaking the destructuring into multiple lines or using named variables earlier for clarity.

let ((a, ), (c, d)) = ((1, 2), (3, 4)); // 😵💫

7. Partial Matching Requires ref or ref mut

let tuple = (String::from("hello"), 42);

let (_, n) = tuple; // moves the String

Use ref to avoid moving:

let (ref s, n) = tuple;

Answers to Questions from the Introduction

The question is whether we can now either find the answerS ourselves or, at the very least, understand what causes the problem and the reasoning of the solution.

Q1

fn main() {

let r = &Some(5);

// `if let Some(val) = r` works even if r is a reference to an Option

// thanks to “pattern matching on references”.

if let Some(val) = r {

// val is a reference to the inner value (&5), since r is a reference to an Option

println!("val = {val}");

} else {

println!("No value found");

}

}

No explicit *r — yet the pattern matches. How?

ris of type&Option<i32>-

- The pattern

Some(val)matches&Some(5)because Rust implicitly treats it as&Some(val). This is part of Rust’s pattern matching behavior on references.

- The pattern

valis a reference to the inner value (&5). Theprintln!macro accepts references, and Rust applies deref coercion automatically when formatting, sovalprints as5.

Q2

Now look at this one-liner:

let Some(x) = &Some(42);

Is this dereferencing, destructuring, or both?

fn main() {

// Create a reference to an Option containing the value 42

let opt = Some(42);

// Destructure the Option using a let statement with pattern matching

// If the Option in not Some, the demo code panic

let Some(x) = &opt else {

// Handle the None case (this block is required)

panic!("Expected Some, found None");

};

// x is a reference to the value inside the Option

println!("The value is: {x}"); // The value is: 42

}

- This is destructuring only. No dereferencing occurs.

- We use pattern matching to destructure the value of

&opt, which has type&Option<i32>. - The pattern

Some(x)is matched against&opt, and Rust implicitly treats it as&Some(x). - As a result,

xhas type&i32— a reference to the inner value. - The

elseblock is required in Rust 2021+ edition if the pattern might not match. - If

optisNone, theelseblock is executed and the program panics.

Q3

One last example. Can you explain what’s going on here?

fn main() {

// Create a Box containing a tuple (i32, &str)

let b = Box::new((42, "hello"));

// Dereference the Box to extract the values from the tuple

let (x, y) = *b;

// Now x and y hold the copied values from the Box

println!("x = {x}, y = {y}"); // x = 42, y = hello

// let (x, y) = b; // Does not compile

}

let b = Box::new(...)allocates a tuple on the heap and returns aBox<(i32, &str)>.*bdereferences the box to get the tuple(42, "hello"), which is then destructured.- The line

let (x, y) = b;doesn’t compile because we cannot directly destructure aBox<T>like that - The compiler does not automatically dereference

Box<T>during pattern matching inletbindings. - We must explicitly dereference it using

*bor use pattern matching withBox(let Box((x, y)) = b;)

Dereferencing vs Destructuring in Rust — Key Takeaways

| Aspect | Dereferencing | Destructuring |

|---|---|---|

| Syntax | *x | let (a, b) = x |

| Semantics | Access pointed value | Extract elements of a structure |

| Applicable to | &T, Box<T>, etc. | tuple, struct, enum, array, etc. |

| Requires traits? | Yes: Deref | No (structural pattern matching) |

- Dereferencing means accessing the value behind a reference (

&T,&mut T,Box<T>,Rc<T>, etc.). It’s about indirection. - Destructuring means unpacking a composite value (tuple, array, struct, enum) using patterns. It’s about pattern matching.

- Dereferencing happens via

*, but is often implicit thanks to deref coercion. - Destructuring can:

- Move or borrow data depending on the pattern.

- Be used in

let,match,if let, function parameters, closures, and loops.

- Patterns can be enriched with:

..to ignore parts,ref/ref mutto borrow during destructuring,- lifetimes when using

&stror references, - match guards, nested patterns, and slice patterns.

- Rust applies automatic deref and matching adjustments in

match, making things feel “magical” — but they are deterministic.

Conclusion

At first glance, dereferencing and destructuring can feel like two sides of the same coin — both seem to “dig into” a value. But their roles are distinct.

- Dereferencing is about accessing through indirection: it gives us the data behind a reference or a smart pointer.

- Destructuring is about unpacking data into parts using pattern matching — whether in

let,match, or function parameters.

Where dereferencing is a runtime operation (or often optimized away), destructuring is a compile-time syntactic feature. And while dereferencing can happen implicitly through deref coercion, destructuring always requires that your patterns match the shape of the data — with the possibility to borrow, copy, or move components depending on the context.

Understanding the difference between the two provides a clearer mental model of ownership, borrowing and data flow in Rust - especially when faced with a “lunar” message from the compiler.

I hope you’ve had as much fun reading these posts as I’ve had writing them. From now on, you should have a clear head and be able to explain destructuring and dereferencing to a buddy (Feynman method). If not, wait 2 or 3 days. Don’t reread the article, but run the examples through Rust Playground. Then link this or that part.

Webliography

- Patterns and Matching in RPL

- Patterns in the Rust Reference

- let statement in the Rust Reference

- Destructuring in the Rust Reference